© Rick Crandall

“I guess all songs are folk songs. I never heard no horse sing ‘em.”

By Bill Broonzy (1893 – 1958)

“I only know two tunes; one of them is ‘Yankee Doodle’ and the other ain’t.”

By President Ulysses S. Grant (1822 – 1885)

Now I like rare. Nonexistent is definitely rare. Think of it, a cabinet automatic piano mixed with a genuine Encore Banjo (see “Encore Automatic Banjo” at https://www.rickcrandall.net/encore-automatic-banjo/) plus drums and traps, all playing the music of early ragtime and dance banjo bands; all encased in oak with art glass and made by Engelhardt, the originator of the coin piano in the U.S. to boot! A number of people have tried to chase this illusory goal, to no avail.

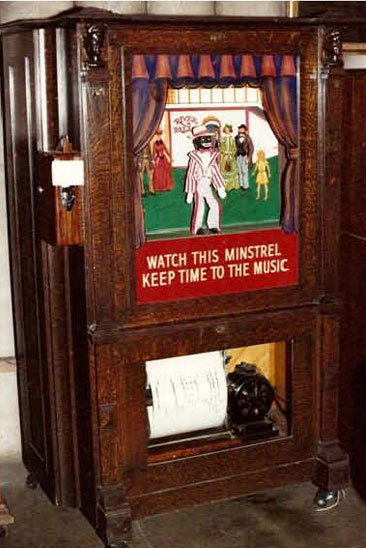

I wouldn’t have even tried to find a Banjorchestra if I hadn’t seen an Art Reblitz editorial in The Coin Slot magazine, January, 1981 issue where he declared the Engelhardt Banjorchestra on his “Most Wanted List.” He said then: “There actually was a machine which contained piano, banjo and drums …a machine which actually existed. Not one example is known to survive today … the stained glass for one is in a California collection … if one is ever found, there is a good chance that it will actually prove to be an ‘Automatic Marvel of its Age.’”

I chased after that California collector – who turned out to be Don Rand. He had purchased a bunch of nickelodeon art glass from a real old timer, Doby Doc of Las Vegas, now deceased. Then I received a cassette tape of an interview Harvey Roehl conducted in St. Johnsville, the home of Engelhardt, where a 93 year old (then in the late 1970’s) ex-Engelhardt/Peerless factory worker recalled actually making Banjorchestras!

Well, I decided that while we may never find a real Banjorchestra, it would still be great to make one and see how it would have looked and sounded. After all, Engelhardt used its Engelhardt F cabinet piano and case as a base and added an Encore Banjo plus art glass – why couldn’t I do the same? Let’s not fool anybody, it would have been a repro, but still a fun project – especially with talents around like Dave Ramey of Chicago (restoration expert, especially Encores) and Art Reblitz of Colorado Springs (also a restoration expert and creates fabulous music for a variety of these machines).

I got really motivated when friend Bob Gilson acquired the art glass collection from Don Rand. Knowing my passion for this project, he graciously offered me the original Banjorchestra art glass. So I then decided to hunt down a Peerless/Engelhardt F cabinet machine. Of course, that wasn’t too easy since there are fewer than 10 of those around that are known to collectors.

It was then young Fresno collector Brad Reinhardt who offered to help chase the Engelhardt F’s located on the West Coast. Brad was ramping up his knowledge of automatic music machines by helping Hayes McClaren (another of the top automatic music restorers in the world) with some of his projects. What I really wanted was a machine that had already been cobbled somewhat so that I wouldn’t feel guilty about deviating from its originality to make up a Banjorchestra.

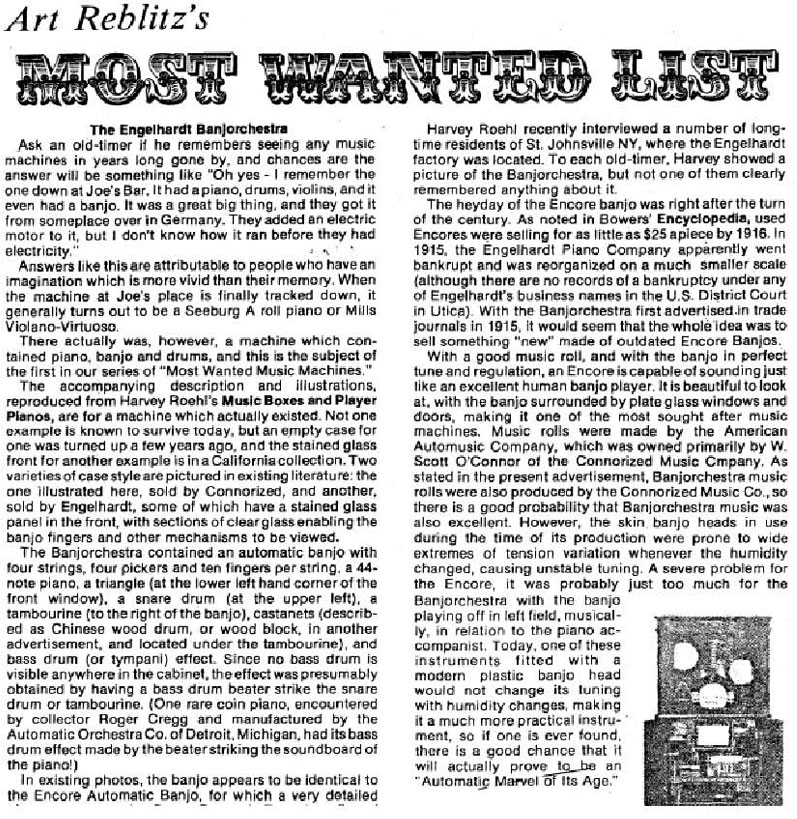

The target machine was the one at Knott’s Berry Farm. Somewhere along the line of its 30 year stay at Knott’s Berry Farm the Engelhardt F had been partially stripped, reconstructed as an A roll piano and a moving scene of a black minstrel player was substituted for the missing glass on the front.

Apparently, at some point the minstrel scene became “politically objectionable” and the machine was also not working reliably, so it was taken out of service and relegated to the storerooms.

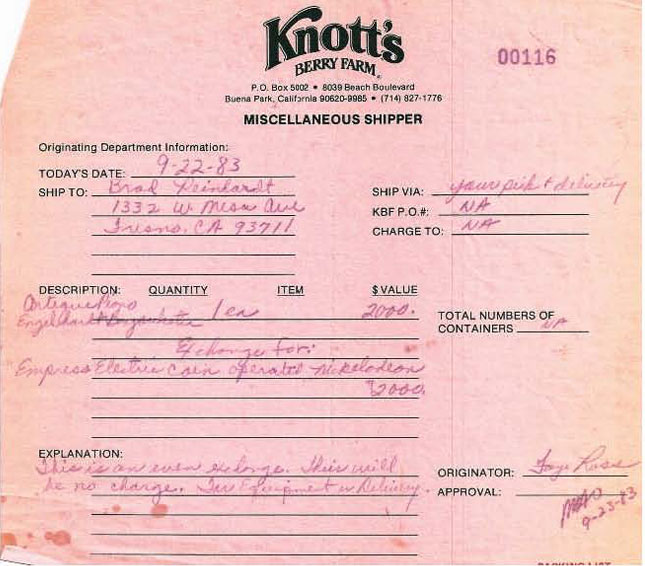

When Brad visited Knott’s Berry to inquire about the machine for me, he heard the oft-repeated pitch that “Knott’s Berry doesn’t sell its inventory.” After much further discussion we did ascertain that they would be open to a trade – the non-working Engelhardt F for a working something that they could put into service.

So Brad hunted down an Empress Electric A roll keyboard piano (“where the keys moved – visitors to the Farm liked to see action”) which we bought and got loaded onto Brad’s truck. Back he went to Knott’s Berry Farm, and sure enough they were still willing to go through with the trade. He unloaded the A roll piano, loaded up the “F” and took off. On the road from LA to Fresno, Brad stopped and got into the back of the truck to take a closer look at the machine. He took the front with the Minstrel scene off and then the plot took quite a different turn.

He rushed to a pay phone (this was 1983, no cell phones) and called me. “Rick, I’m thinking this may be a real Banjorchestra – there is no banjo, but I see clues.” We reviewed them one by one. There was a varnished mounting board on the upper half – there was a semi-circular worn path right where a triangle should have been. Even more exciting was the non-faded area of varnish – that had exactly the shape of the shield-like pair of pneumatic covers on each side of where the banjo neck would be. I told him to look on the lower left for 4 horizontal holes (that would have been where the tuning buttons were for the 4 banjo strings) and sure enough there they were!

I said, “Brad – drive it directly to McClaren’s so we can take stock of what’s there and what isn’t”

The next day I was on the phone with Mac: “It’s a Banjorchestra alright!” he declared. “Somehow in your search to make one up, you’ve found a real one.”

“Not only that – I looked at the receipt Brad got – it was actually listed on Knott’s Berry’s books as an Engelhardt Banjorchestra!”

I knew that Dave Ramey, the king of Encore Banjo restorations and reproductions, was due to be out on the West Coast, and so I had him stop by at Mac’s shop. For those of you who knew Ramey – he was the Mikey of the music world, but he confirmed:“You’ve got some parts missing, but you’ve got yourself a Banjorchestra all right.”

Naturally (for me) I wanted to know more about Peerless, Engelhardt and St. Johnsville. After all, they were the originators of the coin-piano industry in the U.S. and they were also the creators of the Banjorchestra. So with invaluable research assistance from Mrs. Anita Smith, St. Johnsville historian, and others including Dave Bowers and Harvey Roehl, I assembled the story of Engelhardt.

Who Picked Up the Pieces from the Failure of Engelhardt?

The predecessor to Engelhardt was Peerless, a company distinguished by having made the first coin-op automatic pianos (see my article: “Peerless: America’s First Coin Piano Maker” at https://www.rickcrandall.net/peerless-first-coin-pianos/ ). What a tragedy it must have seemed to Frederick Engelhardt, then in 1914 at 60 years of age, whose Peerless Company was going bankrupt in the middle of a boom for automatic instruments. Actually, Frederick had insulated the piano action plant from the chaos, and he continued to operate that business without the help of his sons.

The Peerless orchestrion had been successful almost right up to the bankruptcy, and so there was plenty of inventory in process as well as finished machines. There was also a healthy demand for music rolls that no one else could fill. All Peerless rolls were unique to the machine they were created for.

From Memories of St. Johnsville by Robert Rowland, a town resident of St. Johnsville: “When the whole thing flopped they must have all conked out together and most all families left town, unless they found work around town. Some group started orchestrion work again in the Peerless building; Walt Engelhardt and his father with Bill Kupp started the Engelhardt Piano Company; Fred Kornburst, Elmer Snell and their gang started the National Music Roll Co.”

The first Phoenix that rose from the ashes was the National Music Roll Company, which was purchased and resurrected by Frederick Kornbrust in 1916:

From the St. Johnsville Enterprise:

“Frederick J. Kornbrust … who has been identified with the piano trade for the last twenty five years … and advanced to the manager of the piano and music roll factories of our village, has now purchased the entire plant and music roll business of the National Music Roll Company, together with a tremendous quantity of pianos, automatic players, orchestrions, etc., also the entire stock of material and equipment for the making and repair of all kinds of pianos and musical instruments.”

“The Peerless department of the National Music Roll Company is now running to full capacity and is cutting the very latest and most up-to-date music and is continuing the issue of regular monthly bulletins.”

“The department for the cutting of standard music (probably A rolls) is now making all preparations and will soon resume the cutting of standard music for all styles of instruments.”

“Mr. B.P. Austin, who is a recognized artist in the line of arranging of music, has been permanently engaged as the music arranger for all departments.”

“The automatic and piano parts department for the repair of all styles of musical instruments is under the supervision of Charles Filler, who is an expert mechanic and an authority on musical instruments.”

“It is intimated that plans are under way for the manufacture of a complete line of new types of automatic instruments including phonographs.”

The remaining Engelhardt factories in St. Johnsville were sold at auction on October 11, 1915 for the sum of $36,000 to the Little Falls Fibre Company. The Engelhardts attempted to bid on the plant to try a bigger restart, but lost the bidding. Walter Engelhardt stayed in St. Johnsville and worked with his father, but faded into obscurity. Alfred Engelhardt moved to Chicago in connection with a merger with Seybold (see further below).

Frederick Engelhardt died in August, 1931 at the age of 76. Kornbrust piano and repair business went broke in 1929 or soon thereafter. In the 1928 edition of Fox’s Music Trade Directory there is a note that the Engelhardt Piano Co. established in 1916 was owned by Welte & Co. by 1928.

The companies that tried to go forward from the ashes of bankruptcy in 1915, were:

The National Electric Piano and Roll Co.

The Engelhardt Piano Company

The National Piano Player Co. – which made rolls into the 1920’s with Peerless punches.

From the 1926 Presto Buyers’ Guide:

“The Engelhardt Piano Company of St. Johnsville, NY makes a specialty of the production of automatic instruments embracing orchestrions, banjo-orchestras, player-pianos and reproducing player pianos, bell pianos, flute pianos, xylophone pianos, coin operated pianos, orchestrions, banjorchestras and midget orchestrions.

“The National Electric Piano and Roll Co. – coin-operated pianos bearing this name are admirable instruments in every respect. These instruments are especially suited for theatres and other places of public entertainment. They also manufacture Peerless models, Cabaret, Elite and DeLuxe Orchestrions.”

The Banjorchestra

We have not yet uncovered the specific connection between Alfred Engelhardt and Charles Kendall, owner, or Scott O’Conner, president of the American Automusic Co. of New York, manufacturer of the Encore Banjo. We do know that by 1916 the Encore was way over the hill, the New England factory was defunct and the only thing keeping the New York City Encore Banjo operation going was the receipts from the machines on commission out on location.

There were certainly several opportunities for Alfred Engelhardt to know of the Encore, not the least of which was that for a few years (1898-1900) the Peerless and the Encore were the only automatic music machines available in New York! Whether the American Automusic Co. was acquired by Engelhardt or a supplier relationship was made, Alfred’s business creativity fired his desire to create a true American orchestra with a piano and a real banjo in it. In the 1916 St. Johnsville newspaper, the Engelhardt Piano Co. was formed with the intent in mind to get creative with automatic music.

The result was an attractive “instruments-in-view” keyboardless orchestra with banjo initially encased in a slightly enlarged version of the Peerless/Engelhardt Model F cabinet orchestrion. The Model F has been called one of the most popular of the Peerless machines. In standard configuration it had a piano, mandolin, snare drum, flute pipes or xylophone.

The first Banjorchestra also had piano, snare drum and bass drum effect (beater that hit on the back of the piano soundboard), but instead of a cymbal there was a triangle, wood block and tambourine added and of course the showpiece instrument was the automatic banjo. The Banjorchestra is one of the only instruments with no mandolin (or “banjo effect”) attachment to the piano. Why have a simulation when you’re going to put the real instrument in?

Some recent interviews in St. Johnsville produced some memories of the Banjorchestra. One elderly ex-factory worker was interviewed who recalled building twelve of them. Possibly this was the first run of them in the Peerless F-like case to test the market. They found an immediate market in St. Johnsville saloons. His recollection was that 9/10ths of St. Johnsville was saloons that they called “elbows” in those days.

Mrs. Anita Smith, St. Johnsville historian, wrote on January 25, 1984 that: “a local man remembers seeing the Banjorchestra on display at Mr. Jonas Smith’s Main St. music store; also in storage at his Monroe St. home.” The reader can rest assured that lead has been thoroughly chased as far as it will go.

Engelhardt redesigned the case in a fashion that actually made it reminiscent of the Encore Banjo case except wider to accept the piano.

The Connorized Music Co. became a prominent distributor of the new style Banjorchestra as evidenced by its double-page ads in Music Trades Review.

Engelhardt obviously went to the Connorized Music Co. for roll production. Its president, Scott Conner, would have been highly receptive since he had been the president of the American Automusic Co. (the New York Encore Banjo firm) in 1900 when the original Encore was in its prime. This may have been the connection that resulted in combining a banjo with a cabinet orchestrion.

Or it may have been the other way around. An interesting Music Trades Review, 1914 article has been uncovered by Art Reblitz in which James O’Conner claims to have invented the Banjorchestra:

“BANJORCHESTRA, JAMES O’CONNOR’S LATEST INVENTION”

“President of Connorized Music Co. Perfects Instrument Capturing Banjo, Bass and Snare Drums, Tambourine, Castanets, Triangle and Piano Electrically Operated — Will Fill Place of Many Piece Orchestras Now so Popular for Dancing at Much Less Expense”

“The creative mind of James O’Connor, president of the Connorized Music Co., 144th St. and Austin Place, New York, inventor of many devices which are now in use on musical instruments all over the world, has again been at work with the result that the Connorized Music Co. announce this week the perfection of the Banjorchestra….With the advent of the new dances which have been so popular for the last two years came the rejuvenation of he banjo and other stringed musical instruments of its kind. Orchestras in which the banjo has been the principal have been in demand …

“The Banjorchestra is especially adapted for use in the high-class dancing salons … the banjo and other instruments and traps used in its operation can be plainly seen through a glass in the upper door. The rolls are especially made by the Connorized Music Co. and will be particularly adapted for dancing. “Mr. O’Connor has given great thought and time to the expression and rhythm in the music. So much so that when the instrument starts to play one’s feet commence to shuffle immediately. Pianissimo and fortissimo effects are regulated by automatically controlled expression devices, and automatic muffler being attached to the banjo, and the automatic soft and sustaining pedals being in use in the piano.”

“The banjo is regulation size and is equipped with wire strings. In order to tune the banjo four buttons have been installed in the front panel which, when pressed, sound the notes on the piano to which the open strings of the banjo should be tuned. Arthur Conrow, general manager of the Company, stated last week that they will be ready for orders for these instruments by December.”

The Connorized ad takes license by claiming that the banjo is of regulation size. While it is possible to play the four string tenor banjo, the act is uncomfortable due to the wider neck to allow for the four rows of fret buttons. A clever tuning system of four buttons that sound the four piano notes appropriate to the four open banjo strings (C, G, B, D) is reminiscent of the contemporary Violano Virtuoso with its 4 tuning buttons. The difference is that the Violano enables tuning one string to the piano and the remaining strings to each other whereas the Banjorchestra has you tune each banjo string directly to its piano note, contrary to what a real banjo player would do.

The original Engelhardt promotion of the Banjorchestra was as a jazz band built for durability and serviceability. Various Peerless technologies were abandoned in favor of standard componentry. “All parts standardized and therefore easily interchangeable” says the brochure. “Expression and traps operated direct from the music drawer by special control notes to obtain the best possible effects.”

The Connorized Music Co. had a slightly different market positioning in mind for the Banjorchestra. The idea was:

“The Banjorchestra is a highly artistic automatic instrument which may be used in the place of a banjo orchestra, which has become popular in dancing saloons, owing to its adaptability to the dance music of the day. Perfect rhythm for the modern dances has been worked out in the music rolls … all the expression which is put into the music by the most extensive banjo orchestra is reproduced by this instrument.”

Music rolls were of the 10-tune rewind type with stops in-between each tune. The coin mechanism could accumulate up to 20 coins storing up that many plays to be made in succession without constant attention. “Popular songs and dance hits” were the prevalent fare in the music rolls.

Whenever the Banjorchestra is referenced in the literature, emphasis is given to its expression capabilities. The only unusual expression feature is the automatic mute (or “muffler” as one ad calls it) on the banjo – actually pincers that press against the side of the bridge.

The art glass is designed in an unusual fashion in concert with the method for achieving expression. The leaded outline of the banjo head has no glass – the spaces are open to permit maximum sound transmission. Softer expression is implemented with the mute so that swell shutters that might have blocked the view of the banjo action, are avoided.

Enter Seybold

Once again the bank withdrew its financing, causing a search for new money. One comment that Anita Smith turned up indicated that “Seybolds were Jewish and Engelhardt thought they had lots of money;” So a merger was quickly arranged with Seybold, however Seybold turned out to be worse off than Engelhardt!

From the History of Seybold Pianos by E. C. Alft of Elgin, IL, 1981: “The Seybold Reed-Pipe Organ Co. was founded in Chicago in 1902 by William Seybold. The firm was moved to Elgin in 1903. By 1908 the firm had prospered and extended its product line, and changed its name to the Seybold Piano and Organ Co. By 1910 the plant was employing about 80 people and had produced ten thousand instruments since its founding. Many of its instruments were player pianos priced from $475 to $750.”

“In approximately 1914 Seybold entered into an ill-fated merger that year with the Engelhardt Co. of St. Johnsville, New York. The Engelhardt firm made the Peerless player attachments and bought the piano cases, while Seybold had been making cases and purchasing the attachments. The merged firm was called the Engelhardt-Seybold Co., with its main offices located in Chicago. Fred Engelhardt succeeded William Grote as president. Engelhardt-Seybold declared bankruptcy in July, 1915. Nearly 100 employees lost their jobs.”

From Anita Smith

“I researched the 1917 issues of the St. Johnsville newspaper. There was hardly any mention of the Engelhardts, just as if the family had dropped off the face of the earth.”

“One interviewee was Julie Frank (Julius) born 1890 and started work in 1907. Repaired machines in NY, Penna, and NJ – Victrolas killed off the coin pianos; pay was $1.25 – $1.75 per day.”

The Banjorchestra is listed on Engelhardt letterhead as late as April, 1929 although this was probably misleading since the company was in fiscal decline and may not have been selling any goods by then.

The Banjorchestra Restoration

This Banjorchestra was the first of its kind to be found, and while it suffered no water, worm or other abusive damage, it was missing the banjo, percussion instruments and the front art glass. That could have been fatal to a faithful restoration if it weren’t for the fact that the banjo and picking mechanism was originally lifted intact from the Encore Banjo and at least there are about 19 of those around plus a lot of original documentation and restoration expertise.

Quite a lot was present in the machine, although that was certainly not apparent when the machine was languishing, disguised by its painted glass scene that had been added later for novelty. Much of the mechanism was present, including the case, pump, piano stack, banjo stack, roll frame and many other items including, for example, the “bass drum effect” which we many otherwise never have guessed how to replicate.

Also, fortunately, previous repair work had not included any interior refinishing, so all the original tracks in the varnish were present which helped point the way to where missing components were mounted. As earlier mentioned, the “swing” marks of the triangle and the “badge” shape of the maple pneumatic cover for the banjo fret mechanism that surround the banjo neck were clearly discernable. There was no original music, so the project was exciting because it needed the talents of several of the best experts in the field.

There was also a good bit of luck involved. The story was already told of the acquisition of an original art glass for exactly this style of Banjorchestra. Many thanks to Bob Gilson for making that happen. He is the kind of collector and friend that we need more of in this field.

Dave Bowers also rose to the occasion by finding and lending the only known piece of literature that depicts the pertinent style of Banjorchestra. This piece confirmed what the markings in the current machine were telling us about instrumentation and positioning.

As mentioned in a previous article (“The Encore Banjo”), an original banjo from an Encore had surfaced in a Connecticut music store. I bought it faster than you could say “how much?” and had it in my collection for several years waiting for some kind of fateful use. Also mentioned in that article was the stash of Encore parts found by George Battley of Washington D.C. Most of them had gone to Dave Ramey, but Battley still had some left and there were quickly snapped up by my voracious hunt for original parts. That provided the original fret buttons and some other parts. Others came from the remains of the Ramey acquisition.

There were still a few mysteries. The literature spoke of banjo expression being provided by an automatic mute device controlled from the roll. We’ve known that the Encore originally advertised a manually applied mute to reduce the volume for quieter locations, but none have surfaced as yet. Muting a banjo is accomplished by squeezing in on both sides of the bridge. Likely, the Encore mute was some kind of spring-loaded or adjustable clamp connected to a pneumatic.

Music Box Society historian Fred Freid came to the rescue by lending me an extremely fortuitous two page 1916 ad for a Banjorchestra that actually had pictures of the internal mechanism, front and rear views! While the style of machine was different than the one being restored, the instrumentation was nearly identical except that castanets replaced the earlier wood block.

The Freid contribution gave further proof that the “snare drum” was an Encore banjo head beat from behind.

Blow-up photography solved the mystery of the banjo expression device. A metal pincers pushed on each side of the bridge with padded ends as one might do with their fingers or with a clamp on an Encore, except in this case the pincers were under automatic control from a hole position in the music roll.

So the contributions were many to this project. The restoration was done by Dave Ramey, who was not only one of the best, he’s surely the most experienced in Encore restorations (and reproductions).

The final effort was to create music. It would be nice if an original roll shows up some day, but so far no luck (or maybe good luck, since Art Reblitz has taken up the task of creating music for the machine).Reblitz and Ramey visited my home one day for purposes of figuring out the roll and tracker-bar layout in order to “wire” the machine properly (actually pneumatic tubes carrying vacuum to pneumatics controlling every function of the machine).

We had an experience not unlike the old movie “Blowup” in that we noticed that the ad for the machine referenced and shown earlier in this paper actually showed the Banjorchestra with the lower doors open. That exposed the roll frame and a portion of the music roll – just a portion. I blew that up as far as it would go and from that Art started deciphering what was going on! He actually joked that if he’d had another 12” of the music roll he might even have been able to tell me the tune!

Here is the blowup.

So Ramey and Reblitz partly deciphered the old photo and partly invented a tracker bar layout that has since been the basis for 13 rolls of ten tunes each with great music.

The tracker bar layout is:

1. Play (cancel, rewind)

2. Banjo soft (lock)

3. Piano soft (lock)

4. Banjo/Piano switch (chain perforation):

switches hole 56 from rewind to piano high note B

switches holes 57 – 66 from banjo C string frets to piano high notes C – A

5. Sustain (chain perf.), cancel holes 2 and 3

6. Bass drum

7. Castanets, single stroke

8. Triangle, single stroke

9. Tambourine, reiterating

10. Snare drum reiterating

11. Snare drum single stroke

12. Piano bass octave coupler off (chain perf.)

13 – 44. 32 piano notes (plus 21 notes from holes multiplexed from above)

45 bass drum

46 snare drum

47 snare soft

48 triangle

49 tambourine

50 wood block

51 – 94 banjo frets and pickers

95 banjo soft

96 shut off

97 rewind

98 beginning of roll

This is implemented on a 11 ¼” roll which worked precisely with a Welte 100 note tracker bar (9 holes to the inch) which would not be surprising since Welte and Engelhardt had a close relationship eventually resulting in Welte’s acquisition of the Engelhardt Piano Company in the 1920’s. The more we study the field of automatic music, the more linkages we find, especially when the going got tough against the advancing technologies of the phonograph and the jukebox.

Notes from Dave Ramey Jr.’s Paper: “The Rebirth of an Obscure American Orchestrion” 1994.

The music rolls have to be especially arranged. Reblitz uses original Encore banjo rolls as a base for arranging new music as well as creating totally new arrangements for the machine. Unlike most American coin pianos, the music rolls for this machine are arranged to be played exclusively on this machine. This allows the arranger the freedom of not having to compromise his composition to make sure it sounds OK on a variety of machines. The end result is a quality of music unlike anything ever heard from a coin piano.

The Restored Engelhardt Banjorchestra

And here it is – playing up a storm – a mixture of ragtime, jigs, reels, dance music and banjo fireworks such as Foggy Mountain Breakdown, one of my favorites.

The case is quarter-sawn golden oak with carved figure heads on top of each column. The art glass is the original with circular opening over the banjo head for sound transmission;

It is coin-operated, played by nickels.

The instrumentation includes a piano (that can be partially seen in the backplane in the photo), snare drum and cymbal (upper left), bass drum (a real one added – upper right), wood block (middle left), tambourine (middle right), triangle lower left, banjo, and castanets (lower right); the roll frame, pump and motor are below.