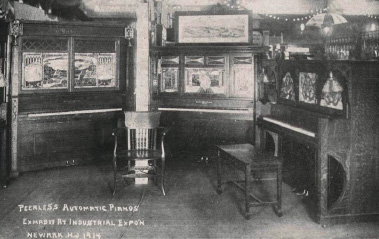

Peerless: America’s First Coin-Op Roll-playing Piano Maker

By Rick Crandall article first published winter, 1987; updated June, 2014

IT’S QUITE A DISTINCTION to be able to lay claim to a “first” in the commercial market place, particularly with a whole new kind of product concept like Edison did with the phonograph in 1878 or like Jobs did with the Apple personal computer 100 years later in 1978. Usually something that is really new and different comes out of the mind of one individual who combines creativity, a sense for market need, an understanding and either access to or invention of the technology and a fortuitous access to funds. When it all goes right, the financial rewards are great.

That was the set of circumstances surrounding Frederick Engelhardt’s creation of America’s first automatic, coin-operated, paper-roll-playing piano in 1902.

Actually, he placed two versions of an automatic piano on the market in that year: the keyboard Style D and a bit later the cabinet Style 44. The cabinet style proved to be a long-lasting success that fueled the rise of the Peerless line of automatic music machines.

To be sure, the idea was not without precedent.

The Encore Banjo (see: https://www.rickcrandall.net/encore-automatic-banjo/) was conceived in 1893, was on the market in the United States in 1897 and had a very successful run for over a decade. Wurlitzer had a barrel-operated coin-op piano, the Tonophone, made for them by the DeKleist Musical Instrument Mfg. Co. of North Tonowanda, NY in about 1898 which was quite successful, although the barrels where quite large and unwieldy. The phonograph industry had a viable coin-operated device since about 1890 and coin-operated music boxes were on the market since 1895.

The coin-operated piano was needed since the phonograph and the music box both lacked the musical power to be heard in a room filled with people, hence not well suited for commercial establishments. Later the simple automatic piano evolved into the automatic orchestras with added wind pipes and percussion instruments that became popular in the 1910 – 1925 period.

There’s a fair amount of information around on Peerless, but its history is confused, it was tangled in a bunch of company names and mystery surrounds its early failure in 1915. I became interested in researching the Engelhardts after having found the first surviving example of an Engelhardt Banjorchestra, a cabinet orchestra containing an Encore Banjo, a piano, drums and traps. This machine has provided great new musical delights since its restoration (see https://www.rickcrandall.net/engelhardt-banjorchestra/). It has also provided the pattern for over 60 quality replicas created by the D.C. Ramey Piano Company.

In preparation for that article, I funded research by Mrs. Anita Smith, a resident of St. Johnsville, New York, the home of Peerless and the Engelhardts. She interviewed old timers and she scanned the local newspapers from 1900-1917. After all that, I still have questions, but I’ve also got a bunch of answers. Others have also contributed to this effort including Hayes McClaren (an avid Peerless collector), Brad Reinhardt (who dug through a lot of Music Trades Reviews), Art Reblitz (author, historian, restorer, music arranger and document repository), David Ramey (who restored the Peerless Style 44 that had been in my collection), Ron Bopp (who has studied a variety of Peerless music), Mr. E. C. Alft (Elgin historian and Seybold researcher) and Harvey Roehl (who preserved several Peerless factory worker interviews on cassette tapes).

Frederick Engelhardt—”He Started It All”

There is always a driving force behind any inventive enterprise. In the case of Peerless automatic music machines, there is no doubt as to the identity of that person. Frederick Engelhardt was born in Mecklenberg, Germany, on June 15, 1855. He came to the United States with his parents as a lad of eight years of age in 1863. Frederick pursued his schooling in New York City, New York, until the age of 11 at which time he began a career in cabinet making.

By the age of 18, Engelhardt was finding it very difficult to get work, and so he enlisted in the U.S. Cavalry in 1873. During his four-year stint he was stationed in several army posts in what was then called the “Wild West,” the Dakotas and Wyoming. Engelhardt obituaries in the St. Johnsville local press had access to his extensive collection of press clippings from those days. Surely Frederick Engelhardt was Americanized after these kinds of experiences documented in the clippings:

“He became acquainted with “Wild Bill” Hickock when he witnessed a shooting exhibition in a Fargo, North Dakota saloon. He saw Wild Bill perforate a nine of hearts with a six-shooter, each heart being shot away accurately.”

“He was with General Terry on the relief to General Custer. They arrived the day after the Battle of Little Big Horn in Wyoming. They learned that the day before (June 25, 1876) the entire detachment of 264 men had been massacred including Custer, whose heart had been removed. The Indians believed that such an action was good medicine since Custer was such a brave man.”

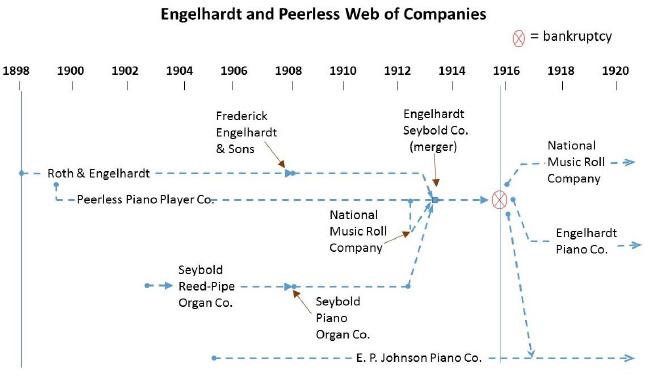

Figure 1. The complex web of automatic music companies associated with Frederick Engelhardt.

Retiring from the army in 1877, Engelhardt returned to New York and entered the employ of Alfred Dolge. A well-known piano maker, Dolge lived in Brocket’s Bridge, later re-founded as Dolgeville. In February, 1881, Engelhardt married Dolge’s sister, Selma. By December of that year he had his first son, Alfred, and three years later his other son, Walter. Both were to figure in his piano business.

Frederick’s penchant for enterprise first surfaced in Dolgeville when he observed that all piano makers were making their own sounding boards. He decided to make the piano sounding board a product all by itself. Dolge successfully began supplying these to other piano makers.

At the turn of the 1880 decade, Frederick Engelhardt decided to strike out into new horizons. He moved to New York City where he landed a job at the Strauch Bros. piano action plant on 10th Avenue. He soon left in favor of a better job as foreman of the action department of the famous Steinway and Sons. Perhaps it was at Steinway that Engelhardt refined his strong commitment to quality, for that was to be a trademark of his work thenceforth.

He remained with Steinway for seven years. During this time Engelhardt’s entrepreneurial itch became unbearable. He dreamed of making his own pianos.

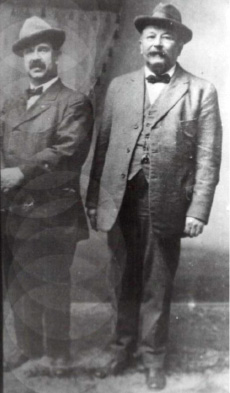

Figure 2: Frederick Engelhardt (left) with Benjamin Austin, Peerless’ master music maker. This photo is from Austin’s album under which was written by Mrs. Austin, “Ben and the big noise.”

Roth and Engelhardt Company

In January, 1889 Engelhardt met up with another entrepreneurially-minded individual, Alfred P. Roth. The two formed Roth & Engelhardt, a small piano action plant at 11th Avenue and 36th Streets in New York City. Within months, the building that housed them was gutted with fire.

That did not thwart the two entrepreneurs. In fact, it caused them to rethink the whole idea of location. Engelhardt must have thought back to his Dolgeville days. He settled on nearby St. Johnsville, its advantages included proximity to a barge canal for lumber and two railroads for shipping. One newspaper ascribed to him the opinion that being a few hundred miles closer to Chicago, Illinois, put him nearer to the biggest consumer market for pianos.

Fig. 3: First Engelhardt action factory, Bridge St., 1889.

Roth and Engelhardt procured a small factory building in St. Johnsville and hired 11 hands. Then they selected the site of an old cow pasture and quickly built their first real factory building. It was a two-story building that was 30′ x 210′ in size. Indications are that they purchased the rights to Fred Goolman’s “Autono” as a kickstart. Years later there would be legal problems with Goolman. Within weeks of the opening the number of hands grew to 115. Part of the funding was $10,000 raised from St. Johnsville itself.

Engelhardt’s credibility was high and the venture seemed sure to bring employment and industry to St. Johnsville. Roth was the more silent partner of the two. He remained in New York City and conducted the finance and administrative affairs of the company. Engelhardt was in charge of the research, operations and merchandising.

The opening of the factory was a big event in St. Johnsville. Seven hundred invitations went out throughout the environs, each invitation being engraved on a small block of maple.

The attitude of the townsfolk was reflected in the Little Falls Evening Times, May 1, 1890:

“While the opening was a remarkable success viewed from a social standpoint, it had much deeper significance. This factory is converting St. Johnsville from a dead town into a live progressive village. The effect of the new concern on the village has been electrical. It has awakened business and created enterprise. It is as good as a gold mine to secure the location of such a firm.”

Figure 4. Frederick Engelhardt’s St. Johnsville home.

There must have been an ongoing need for piano actions. Either that or Frederick Engelhardt was a natural-born marketer because demand quickly outstripped supply. A 40′ x 140′ factory addition was built in 1891 and another 40′ x 150′ addition was constructed in 1893 at which time employment was at 150 men. The latter enlargement included some kilns for drying wood. Logs were imported from only 12 miles away, cut in the spring and fall, sawed in the winter, aged two to three years and then dried for four to six weeks in the kilns. Roth and Engelhardt became very vertically integrated in so far as the piano actions were concerned. They would send their actions out to an as yet unconfirmed piano manufacturer for completion. Roth and Engelhardt may not have ever actually made the piano itself.

During the early 1890’s an experiment was attempted having a western factory in Chicago Heights, Illinois. However, the economic recession that hit the Midwest was blamed for softer demand which, in turn, forced the closing of the auxiliary factory at the end of 1892.

The Advent of Automatic Pianos

The years 1898-1902 were one of the most important periods in the history of the automatic music instrument field in the United States. That was the period the early entrepreneurs created the automatic piano business. Roth and Engelhardt were the first to apply paper music roll technology to coin-op pianos that made national distribution of automatic music machines and their music practical and economic.

Frederick Engelhardt often travelled to Germany. He belonged to the school of thought that required apprenticeship as a necessary step toward success. Engelhardt learned every detail of the piano business. He travelled to the “Old Country” where he donned overalls and toured the German factories. There he observed that automatic music instruments were achieving some popularity. He thought America could be cultivated with similar results. So, while we cannot credit Engelhardt with the absolute creativity of conceiving the roll-playing piano idea, we can give him kudos for sensing an opportunity, capitalizing on it and creating the market in the United States.

He did customize the idea to the American market. The early European automatic music machine market was very much oriented to classical selections played on organs with a diversity of pipework. In contrast, Engelhardt’s first two products were simple self-playing pianos of limited scale and with simple, popular musical arrangements. Blues, rags, piano characteristics and other hit tunes populate the early rolls. There was to be little classical music for the rough-and-ready American market.

A closer study of patent filings might produce answers as to who the actual inventors were for the various pneumatic and roll operation mechanics were employed in their early machines. We see that in 1901 Frederick Engelhardt filed a patent (#689,864) for an improvement in “Autopneumatic Piano-Players … relating to means for operating the piano pedals either by the perforated music sheet or by hand, and means for controlling the expression of the instrument” both of which are important refinements to musicality. That indicates that at least some of the invention came from Engelhardt himself.

Peerless Expansion

Factory expansion proceeded with the acquisition of the Bunce and Benedict factory where a straight piano called the Petit Bijou had been made since Sept, 1890. The Petit building became the Roth and Engelhardt Building Number 4 in 1902.

Fig. 5: The Petit building of 1898 right on the railroad tracks.

Meanwhile, the piano action business boomed. Roth and Engelhardt became widely known for its quality actions. In a July 25, 1901, local newspaper article, the firm of Roth and Engelhardt was described as employing 234 people and operating the largest piano action factory in the world producing 1,037 actions per month.

In 1901, at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, NY, Roth & Engelhardt won a gold medal for their Peerless Pneumatic Electric Piano Player attachment (a pushup player), another gold medal for their Harmonist Foot Pumper Piano Player and a silver medal for their piano action.

Peerless Style D, the First

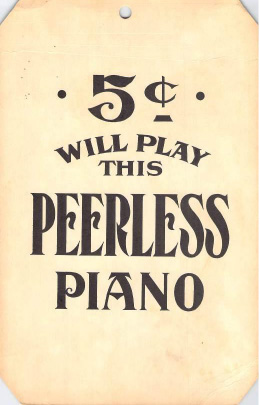

Between 1901 – 1902 the Peerless Style D keyboard roll-operated piano was introduced. I believe the Peerless Style D has the distinction of being the first automatic roll-operated piano. While it did not have a coin slot integrated in the case but there was an add-on coin box we’ve seen mounted on the side of the piano. This might indicate Engelhardt was aiming at both the home and commercial markets with the Style D.

Fig. 6: Peerless Style D

It plays an endless “D” roll (11 ¾” wide, 6 holes/inch) with the roll frame mounted behind the piano sounding board requiring the piano to be located away from a wall. The roll played 65 piano notes plus control for hammer rail and sustain pedal. This style was long lasting and reappeared in 1909 in a Mission-style case.

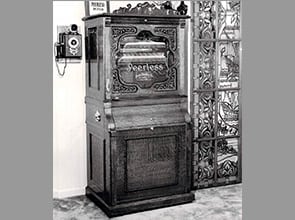

Peerless Style 44

Shortly after the Style D, a keyboardless cabinet machine called the Peerless Style 44 was introduced. The Style 44 is an attractive, diminutive machine with the piano playing 44 notes, hammer-rail control and no automatic mandolin. The roll is 8 ½” wide and spaced 6 holes/inch. The Style 44 actually bore a resemblance to the Encore Banjo, particularly in its endless roll format, roll re-winder, case style and metal trim. A 1903 newspaper account indicated that Engelhardt piano cases were made in New York City, but were to have been taken over in St. Johnsville once a new factory building was completed. Perhaps whoever built the Encore cases in New York City also built the early Engelhardt cases.

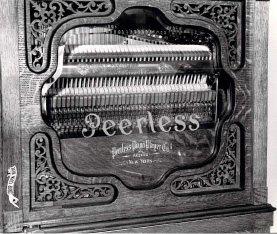

Fig.7: Peerless Style 44 (#780), Crandall Collection

The Peerless Style 44 is definitely a unique instrument. Its endless roll system was patented for its ease of removal from the piano for quick roll changes even when the piano was playing. While that was a stated feature, removing the bin while the machine is playing would be a noisy venture resulting in many uncoordinated notes playing at once along with the shut-off being activated.

The coin slot is different in that it uses a double-barreled coin chute to direct nickels one way to start the machine and pennies are diverted to be kept, but ignored.

Fig. 8: Removable roll bin endless roll frame is on top.

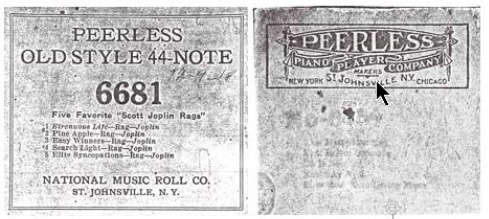

The music uses no mandolin rail and simply supports hammer-rail expression. The music found for the Style 44 is the earliest found on any coin piano. Some of the titles of the coon songs are 20 to 30 words long and racially inappropriate. One roll has all Scott Joplin rags and others recall to life a wide variety of ethnic music. The arrangers got quite a bit out of a 44-note range.

The builders took the time to hide the wires to the interior light socket by channeling the side of the machine, laying the wire and veneering over it! The corner lattice works are made of wood, but are of a similar idea to the earlier brass grills on the Encore. The overall appearance of the machine is definitely attractive and diminutive with the piano action fully in view through glass that is scalloped, beveled and carries the Peerless name etched in the middle of the glass.

Fig. 9: Peerless art. All this is found on this little piano front: “Drop Coin” decal, beveled, scalloped and etched glass, earlier “Roth & Engelhardt” hammer rail decal and Peerless pneumatic stack cover decal.

Earlier Peerless machines had a Roth and Engelhardt hammer rail decal. Later Peerless Style 44’s switched to an Engelhardt and Sons decal. Also, many of these machines were converted to play Pianolin rolls with a Pianolin roll frame mounted sideways. These converted machines retain the overall appearance of the Peerless but they do not play Peerless music.

Fig. 10: A Peerless 44 converted to play a Pianolin roll.

Indications in press coverage are that market reception to these first two automatic pianos was enthusiastic and resulted in strong sales.

Enter the Engelhardt Sons, Exit Roth

During the period of 1900-1902, the two Engelhardt sons, Alfred and Walter, had begun to work in the factory. Alfred at age 18 was the first to become part of the enterprise at the turn of the century. He studied and made piano actions, but he found the player mechanisms far more interesting. Walter also gravitated toward player construction. He was more inwardly directed, less gregarious. Walter had few friends, and allegedly, no one liked him. Of the two, he was even more committed to the player piano business. As Alfred rose through the ranks, he became known as a troublemaker. He was “one of the boys” who got into various kinds of mischief and who enjoyed the power and benefits of corporate rank and position.

In 1907 Roth decided to retire. He sold his stake in the business to Frederick. The name of the firm was changed to F. Englehardt and Sons and Alfred and Walter got some ownership. F. Engelhardt and Sons concentrated its business on actions and the supply of components to the trade. The Peerless Piano Player Company was incorporated to build and sell automatic music machines.

Alfred became the more dominant of the two sons. He took over Roth’s finance and administrative responsibilities, but apparently with far less acumen, and without his father’s penchant for details. The seed for the eventual downfall of the enterprise had been sown.

Walter had gotten into operations and eventually took over the role from his father. Frederick was approaching his late 50’s and was becoming more civic minded. He was elected village president from 1902-04 and again in 1907-09 while continuing to operate the action plant as a separate entity. He also took part in all Masonic events and travelled widely.

Colonel Ray Nellis, an action factory worker during the 1904-1915 period, was one of several St. Johnsville residents interviewed on tape by Harvey Roehl in the 1970’s. Nellis recalled:

When he (Frederick) ran for office, he didn’t even need an electioneer. He won the election. He bought everyone a drink after he won. The town was nine-tenths saloons that every [one] called elbows.

The Engelhardt’s became star socialites in town. They held enormous New Year’s parties, enjoyed chauffeur-driven Stutz Bearcats and even provided St. Johnsville with electric power for lights from the factory’s steam generator.

Frederick was known as a nice and well-liked man who was strict, but fair. He was neat and fastidious with a strong commitment to quality. He was definitely a conservative. Mat Rapacz, trustee of the St. Johnsville library reports: “I did find a May 12, 1903 newspaper article indicating that he (Frederick) locked out 150 workers because they formed a union!”

One recollection of him put it this way:

Mr. Englehardt, at the height of his power, wielded an immense influence. That he was guided by a desire to do the right thing, none will dispute. In the main, he was fairly well supported by the village. In some things, he made enemies because of his lack of that peculiar tactfulness essential to the born politician. He had plenty of courage, was a master of himself and never sought sympathy.

His sons were not such fundamentalists, particularly Alfred, who had stars in his eyes about the ease of corporate expansion.

The player instrument business boomed and by 1907, a large brick factory building was being constructed just for automatic music machines. The factory was founded in February, 1908, and was heralded as the most advanced manufacturing facility for automatic music.

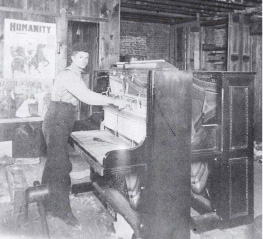

Fig. 11: Peerless final assembly factory area. Machines from right to left: Peerless Style 44 with front removed, Peerless D, Peerless A orchestra, two early Peerless orchestras with exterior drums, some unidentified machines in the rear.

So by 1910 there was an action factory, a key factory, a music roll factory and a player factory. The cases for the machines were made by the woodworkers in the action factory. The art glass was purchased from an outside source in assembled condition. Engelhardt made every

Fig. 12: Images from Engelhardt’s 1904 Piano Factory

internal component in-house— the actions, sounding boards, cases, and pneumatics. Adirondack maple was

selected personally by Frederick Engelhardt and air dried for at least two years before use.

The 1900-1910 decade was certainly a time when the Peerless name was paramount in coin-operated machines.

Peerless Model Variations

Engelhardt made basically two lines of music instruments, the Harmonist player piano and the Peerless coin-operated machines.

The Harmonist was made in four styles: one each of a foot-powered and an electric cabinet player and one each of a foot-powered and an electric interior player. Gold Medal Awards were won by the Harmonist at the Pan American Exposition, Buffalo, New York, 1901; World’s Fair, St. Louis, Missouri, 1904; Lewis and Clark Exposition, Portland, Oregon, 1905; and Jamestown Exposition, 1907. Rolls for the Harmonist were made by Engelhardt and apparently some were encoded for automatic expression. The 1910 Presto Guide claims that some styles of Harmonist had “an improved device which controls the expression automatically or under the direction of the performer at his option.”

Fig. 13: Peerless 1909 Calendar Featuring the Harmonist

Trying to track the various models produced under the Peerless name during its 1902-1915 life span is a difficult task. Little has been discovered by way of a catalogue series. We must rely on local newspaper announcements many of which lacked the kind of technical details today’s collector would like to know.

Peerless instruments that are known or are described in the literature In addition to the Style D and 44:

Style M—a 6 ½ octave piano first appearing in the spring of 1906. The forerunner of the DeLuxe orchestrion, but with push buttons instead of coin-slot activation; used as a theater photo player.

Peerless Automatic Piano— introduced March, 1909. Coin-operated piano.

Style D-X Peerless — introduced March, 1909. Piano plus bass and snare drums (single beater, adjustable, loud or soft), voiced loud. The D-X roll is an extension of the D roll, endless and 11 ¾” wide, but spaced 6 ½ holes/inch. Some unique Peerless machines have also surfaced including a DX model in the Hayes McClaren collection with exposed drums mounted on top of the case.

Style D-M — unknown, possibly the same as the Style M but including a melophone playing the extra instrument.

Style A, Design IX — available in 1910, tall case, keyboard model orchestrion, plays D-X rolls.

Fig. 14: An ad from the Music Trades Review showing the Peerless DX orchestra with exposed drums. Interestingly it was made concurrently with enclosed orchestrions.

Style RR — introduced July, 1911. “Piano with easily accessible action. Each power pneumatic can be adjusted independently to take up lost motion of the piano action proper (also found on other Peerless models). 20 selection music roll.” The roll is 11 ¾” wide with 73 holes, 66 notes plus sustain and one or two extra instruments, but no drums.

Style F — a cabinet machine available either as a piano, or a piano and xylophone or a piano and pipes, playing the RR roll. The Style F cabinet was the predecessor design for a similar looking, but larger cabinet that encased the Banjorchestra.

Style V — unknown, playing the RR roll.

Model Cabaret — unknown, playing the RR roll.

Style D-F — unknown, possibly the same as the F.

Model Elite — introduced March, 1909. Uses a large 14 ½” roll containing 97 holes at 7/inch in order to play a full 88-note piano with mandolin and expression, optionally equipped with flute or demands of discriminating buyers for use in places where the so-called automatic piano was objectionable. “The Model Elite is equipped with a volume subduing device which is perfect, whereby the volume of tone can be regulated to suit the size of the room in which the instrument is placed.” It is also an ideal instrument for the house for it can be controlled by means of push buttons placed in any part of the house.” Elites that are found today are usually seen converted to the later 65-note format.

Wisteria — 88-note piano plus violin or flute pipes, castanets and triangle (some have been found with a woodblock as well), playing the O Roll.

Arcadian — 88-note piano, 32 violin or flute pipes (some have been found with both), bass and snare drums, cymbal and triangle, tympani and violin pipes. “Entirely new departure in coin operated pianos. It is designed to meet the crash cymbal effects, castanets and mandolin, playing the O Roll.”

Fig. 15: Peerless Arcadian in Original Location

Fig. 16: Peerless Arcadian (left), Style A (middle), unknown model on the right.

Style O “DeLuxe”—introduced in March, 1909. A wide 14 ½” rewind roll playing an 88-note piano by playing 66-notes and the rest with bass and treble octave coupling, 78 pipes for violin, flute and cello (the latter are five violin notes in the high end of the 4′ range), bass and snare drums (the snare has three beaters), cymbal (which operates independently of the bass drum) and triangle, tympani and crash cymbal effects, castanets and mandolin.

Fig. 17: Peerless Style O “Deluxe” Orchestrion in the Hayes McClaren Collection

Style Trio — introduced March, 1909. A small coin- operated piano orchestrion in a keyboardless rectangular case. The upper front has two doors with art glass panels with the name “Peerless” in each. Its two ranks of pipes are symmetrically arranged. The Trio roll is an 11 3/4 ” wide rewind roll with 57 holes containing the Peerless Style 44 note scale with additional perforations for pipe control and rewind. This seems to be a forerunner of the machine referred to as “New Peerless 44.”

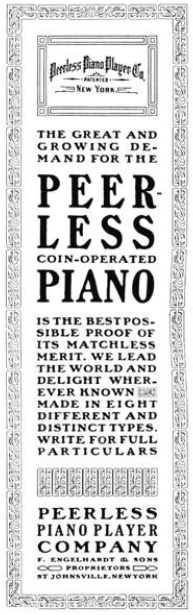

Market Regard for Peerless

Peerless machines were highly regarded for their quality of manufacture as evidenced by glowing praise from noteworthy sources:

The Eilers Music Co.:

“Wish you would kindly notice the brass tracker board I have just taken off of an electric piano playing out of doors from morning until late at night for nearly 30 months. . . The entire action of the piano was in A-1 shape and certainly shows up to anybody’s satisfaction the durability of the Peerless piano.” March, 1909.

Another dealer said: “We have had considerable experience with the electric piano proposition and, in our judgment; the Peerless electric pneumatic piano is, in the line of electric pianos, what the Steinway is to the line of regular pianos.”

Grinnell Brothers, Michigan:

“We feel the Peerless is the best electric piano made, in appearance, workmanship, ability and tone. We sell several electrics per week in Michigan.” 1911.”

The 1910 Presto Guide claims:

“These instruments were widely introduced when twelve of the sixteen battleships that went around the world for Uncle Sam were fitted out for that memorable cruise with Peerless players.”

A 1910 Music Trades Review article recounted:

“A climax of the success scored by the Peerless came when the instrument, after being exhibited at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (in Seattle, Washington, in 1909), won high honors, the International Jury of Awards going on record (with typical exaggeration) as follows:

‘The exhibit of F. Engelhardt and Sons represents the highest development in the construction and ‘This firm deserves the highest commendation manufacture of electrically operated piano for originality in design and high standard of mechanisms. The apparatus in acting solely upon excellence in the manufacture of the Peerless the pneumatic principle does away entirely with endless roll electric pianos.’ springs and friction of every kind, producing a natural human tone, besides insuring the greatest durability.”

Figure 18. Ad from the 1910 Presto Guide

Roth and Engelhardt vs. Automatic Music Company (Maker of Link Pianos and Orchestras)

One of the early innovations contained in the Peerless Style 44 piano is the clever way the endless roll bin and attached roll frame can be removed from the machine in one piece without having to fumble with the roll. This allowed the operator to interchange bins from one location to another without handling the roll at all.

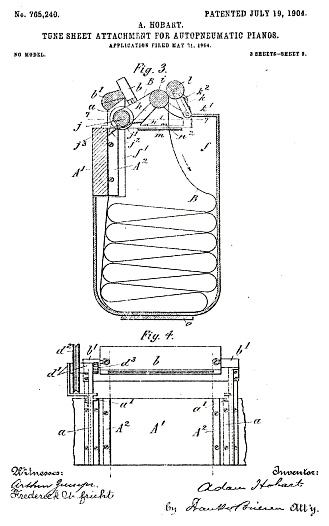

The endless roll system is similar to the Encore Banjo, although Roth and Engelhardt succeeded in patenting improvements to the roll system. An employee, Adam Hobart, was listed as the patentee (#765,240 issued July 19, 1904) for “improvement in tune-sheet attachments for auto-pneumatic pianos.”

Indeed, Adam Hobart was the technical creator of much of Peerless’ unique mechanisms with several patents to his name and assigned to Engelhardt. As regards the Peerless Style 44 patent, Hobart states:

“My invention consists in providing auto-pneumatic pianos with a box which is separable from the piano case and contains the tune sheet rollers. The duct bridge (tracker bar) and the driving shaft for the tune sheet are attached to the piano case proper”.

Fig. 19: One of Adam Hobart’s Patents, 1904

Fig. 20: Distributor letterhead showing the disputed “Reliable” with removable endless roll

bin on the right front.

The Automatic Music Company of Binghamton, New York, had commenced business in 1903 using a similar removable mechanism in its endless roll automatic piano called the “Reliable,” and Roth and Engelhardt decided to play hard ball. In 1906, Alfred Roth, on behalf of Roth and Engelhardt, sued the Automatic Music Company and its then current president, Louis H. Harris, for patent infringement.

A few quotes from the case (which impressively reached the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, 2nd Circuit) were interesting:

“The invention of Hobart relates to a tune-sheet attachment which is separable from the piano case and permits tune-sheets to be inserted readily. When the attachment is secured to the case, a true engagement is at once established between the tune-sheet and the duct bridge (tracker bar) and, simultaneously, the tune-sheet feed roller is inter-geared with the driving shaft.

By arranging and adjusting the tune-sheet in a separate box before it is attached to the piano, he avoids the difficulties which had theretofore existed and which frequently resulted in the tearing and destroying of the sheet.”

Apparently the judge was fully convinced of the lack of credibility of Automatic’s key partners, Harris and Goolman. In a most transparent way of calling someone a liar, the judge said of Harris and Goolman: “The most charitable view to be taken of the testimony is to conclude that the witnesses were mistaken.”

Hobart’s original patent application had been hotly contested over a number of years by Goolman. When the interference case was tried, Goolman, the defendant, tried to change his tune by claiming the Hobart patent was void for lack of patentability. This the judge saw through in concluding: “Men do not struggle for years to secure a valueless thing.”

The court found in favor of Roth and Engelhardt in February, 1909 (reported in 162 Fed. 160).

A few years after this decision, Edwin Link became president and general manager of the Automatic Music Company. Meanwhile, Automatic may well have stopped using the removable roll drawer, but the Engelhardts still had a right to assess damages for past use. The legal effort took three more years in court until finally, on November 6, 1913, Roth and Engelhardt (then F. Engelhardt and Sons) won a big money damage against Automatic for $282,885 plus interest. It is likely that amount was never collected as Automatic was broke by that time.

This was, however, an amount proven to be Engelhardt’s lost profits from the endless roll pianos that Automatic had produced and sold.

The amount helps quantify the number of Automatic Music machines sold from 1903-1909. If profits were $50-100 per machine, then somewhere between 2,800 and 5,500 machines were produced. That is a very successful quantity for an automatic piano during those early days.

Presumably, the Peerless Style 44 sold even more since it hit the market first and had a longer life.

Peerless Music

Peerless advertising stopped short of making the low credibility claims of others that mechanical music was indistinguishable from real human orchestras. However, the benefits of tireless and repeatedly consistent performances were strongly promoted.

Ever since the very early days of Peerless, music arranging was done by the company at the factory by Benjamin P. Austin of St. Johnsville. Austin (see Fig. 2) was an accomplished musician and band leader. He conducted the Peerless Band beginning in 1910 and came to that job with some reputation as a conductor of other orchestras.

A big year for expansion was 1911 and expansion in the music roll department was no exception. A July 26, 1911, article in St. Johnsville News highlighted progress in Austin’s department:

Fig. 21: Peerless Band posing after playing at “Old Home Week” on June 12, 1912, in St. Johnsville. Frederick Engelhardt is front and center.

“Owing to the constant increase in demand for perforated music … moved that department to the larger brick building … formerly owned by Bunce and Benedict (see Fig. 5) is divided into three departments, pattern making under B.P. Austin, music roll cutting under Lester Elwood, and the packing and shipping under George Plank, Jr.”

Plank is referenced in another article as a member of the Peerless Band and “. . . the best handler of drummers’ traps in the Mohawk Valley.” It seems many Engelhardt employees were musically inclined.

The F. Engelhardt and Sons roll department consisted of six or seven perforators that cut six rolls at a time from masters that were hand marked by Austin and hand cut by Elwood.

A modem interview produced a story about early, music-roll paper experimentation. The first paper stock used suffered from the now well-known problem of dimensional instability in conditions of varying humidity. Apparently with early Peerless rolls the problem was so acute that tracking would change between day and evening.

As the story goes, Peerless had 14 coin pianos on location at Coney Island in New York. That was a big customer. Problems developed immediately with the machines and a serviceman was sent several times to fix the problem. At first, no problem was found, until the “hot-under-the-collar” customer insisted the serviceman stay overnight. Then the problem surfaced. The rolls swelled up at night in the absence of the drying effects of the daytime and the rolls wouldn’t track. The customer became fed up and returned all 14 machines.

Engelhardt took the problem to heart and switched paper stock to a “terrafine” waxed paper which solved the problem. Henceforth, Peerless touted the stability of its rolls—even where machines were used on ships.

In the production of music for its machines, Peerless marched to its own drum. An article authored by Ron Bopp in The Musical Box (Christmas, 1981), the journal of the Musical Box Society of Great Britain, disclosed data from an April-May, 1922, Bulletin of “Peerless Rolls for Peerless Automatic Piano and Orchestrions….” Peerless rolls followed a naming scheme that derived from their associated machines. The Bulletin helped further correlate roll names to a numbering scheme:

| Type of Roll | Serial Range | 1922 Price |

| 44 Note (endless) | # 6,000’s | $ 2.75 |

| D, DX, DM (endless)s | # 7,000′ | 2.75 |

| RR, Cabaret | #10,000’s | 4.50 |

| O | #20,000’s | 7.25 |

| Elite (88 note) | #30,000’s | 7.00 |

| Trio | #40,000’s | 4.50 |

| 65 note | #50,000’s | 3.35 |

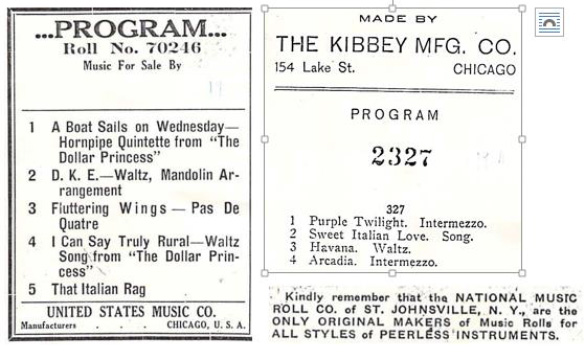

In that article, Ron reports that often the same tunes would be arranged for all roll types. An example is roll #337 (“Favorite Dance Selections”) which was available for Style RR as # 10337, Style 0 as #20337, Elite as #30337, Trio as #40337 and for all 65-note pianos as #50337.

In 1922, the rolls were being produced by the National Music Roll Company, one of the successors to Peerless. There was also a 2000 series of rolls for the Peerless Style 44 which was the earlier numbering used for these rolls by the Peerless Company itself pre-1915.

The earliest Peerless Style 44 note roll I’ve come up with is #2123:

- Reveille, Marching Through Georgia, Soldiers Farewell, Good Night Ladies, Battle Hymn of the Republic

- Swanee River, Dixieland, The Red, White and Blue

- My Old Kentucky Home, Arkansas Traveler

- Hail Columbia, Yankee Doodle, Star-Spangled Banner

Peerless Style 44 music rolls are a study in early American music, Roll #2549:

- Whirlwind Rag

- Gold Dust Twins Rag

- Ten-Penny Rag

- Ragtime Oriole

- Domino Rag

Incredibly, rolls for the Peerless Style 44 were made all the way into the early 1930’s. The latest roll I have on my list is Roll #6932

1. Old Fashioned Garden, one-step

2. Make Believe, fox trot

3. Mello Cello, waltz

4. Bright Eyes, fox trot

5. My Morning, fox trot

The roll number is definitely not a reliable indication of the date of production. Roll #6133 is titled “Broadcasted 1926 Specials (Dance Hits)” while roll #6672 is dated 5-30-18 and is clearly World War I from one of its song titles: When the Boys from Dixie Eat the Melon on the Rhine.

Fig. 22: Rolls were made for the Peerless Style 44 by manufacturers in addition to Peerless itself.

Peerless Success

In 1911 and 1912 the Peerless business was still booming. The two sons had taken over the Peerless automatic instrument business and Frederick stayed with the piano-action business which he continued to keep separate.

Under Alfred’s influence, various expansion plans were executed. The music roll department in St. Johnsville was greatly expanded. In April, 1911, the New York City showroom was moved from Windsor Arcade (47th and 5th Avenue) to the eighth floor of the Mercantile Building on 14 East 33rd Street. There a 2,000 square-foot facility was set up to display a complete line of Peerless machines and Harmonist players.

In August of 1913 a sudden retrenchment move was made with no explanation. The keyboard factory assets and staff were sold, and part of the vacated building was redeployed as additional music roll production facilities.

This move may have been a significant foreshadowing of what was to come. Certainly, the competition was beginning to heat up. At the opening of the 20th century, Engelhardt’s only competition was Wurlitzer. John Gabel had been shipping in small quantities of his automatic selectable-tune disc phonograph called Gabel’s Automatic Entertainer. In 1907 Seeburg entered the fray, Marquette (makers of the Cremona line) and Operators (makers of the Coinola line) were already growing rapidly and Mills entered with the Violano Virtuoso in 1909. Then Berrywood entered the market in 1912. Certainly by 1913 the automatic music field was cluttered and many of the competitive factories were right in Chicago close to major markets. Also, Link had revitalized the Automatic Music Company in 1913 in nearby Binghamton.

Just when Peerless needed a guiding force, Frederick Engelhardt was winding down his involvement in the automatic machine business and his sons were assuming complete control. But the real blow was to occur as a result of an ironic twist.

It was in early November of 1913 that the previously mentioned judgment of over $280,000 was awarded to the Engelhardts at Link’s expense. Surely the availability of this cash once again turned Alfred’s mind toward a long-desired thrust into the Chicago market. Alfred had always felt that a Chicago base was key to effectively competing with the Chicago-based manufacturers. Chicago was to music machines what Silicon Valley is to tech today.

The Seybold Reed-Pipe Organ Co.

With cash in hand, Alfred let no grass grow under his feet. In the very same month (November, 1913), he decided to acquire his way into the Chicago market. A merger was struck between the Seybold Piano and Organ Company of Elgin, Illinois, and Peerless. A new company was formed called the Engelhardt-Seybold Piano Company of Chicago with offices at 316 South Wabash Avenue.

Frederick Engelhardt was listed as president, Alfred was vice-president, Walter was secretary and the Seybold general manager, F. Ackermann, was treasurer.

An article in the St. Johnsville News had this to say:

“The Engelhardt Action Plant will remain the same, an independent institution personally conducted by Frederick Engelhardt, it having been run independently for the past several years. . .general offices (of the new concern) will be in Chicago with other offices in New York City and a newly established office in San Francisco.”

The Engelhardt-Seybold Piano Company had three divisions:

1. The Peerless Player Piano Company which was all of the F. Engelhardt and Sons Company that made the automatic machines, including the St. Johnsville factory.

2. The Seybold Piano and Organ Company of Elgin, Illinois, which was all the business and factory of Seybold.

3. The National Music Roll Company of St. Johnsville which was the music roll production part of Peerless.

Seybold was in some ways similar to Peerless in that it supplied components to the trade as well as full pianos and other products to consumers. Where it differed was that Seybold was good quality offered at a low price, whereas Peerless was medium to high priced. The 1910 Presto Guide confides:

“Seybold pianos are designed for a discriminating buyer who appreciates fine tone qualities and handsome case design, but who do not care to invest the larger sums asked for by the distinguished makers.”

Founded in Chicago in 1902 by William Seybold (1858-1904), Seybold was one of the earlier startups in the embryonic industry of player instruments. William Seybold received a patent for a four-chamber reed box which gave the ordinary organ a quality of tone resembling that of a full pipe organ. Seybold was attracted to Elgin, Illinois, in 1903 by William Grote, a local real estate developer and former mayor.

The move was undoubtedly prompted by William Seybold’s decline and death a year later. At that time, Grote became president and Fred H. Ackermann’s brother-in-law, William F. Bieltmann, who had learned the organ maker’s trade in Germany, was the factory superintendent.

Seybold began production in Elgin with 11 employees. At first, Seybold procured its cases and some other parts from outside suppliers, but by 1905, all the equipment necessary for making its own cases had been obtained. With more than 50 employees, Seybold was then turning out 10 instruments daily and foreign trade was rising.

In 1908 Seybold added pianos to its line and the name was changed to the Seybold Piano and Organ Company. Daily capacity was five pianos and 10 organs. By 1910 the plant employed about 80 (all male except for one stenographer). About 10,000 organs had been manufactured and the plant had been enlarged four times.

By 1913 more than 10,000 pianos had been manufactured and the firm was producing pianos at the rate of 2,000 per year, many of them player pianos. Seybold made the cases, some componentry and did the final assembly, whereas a number of components were purchased from Peerless. Seybold pianos were priced from $200-375 and the players from $475-750.

Grote’s and Ackermann’s rationale for the merger with Peerless is enlightening to collectors who have wondered about the mix-and-match status of surviving instruments of various makes. A late 1913 Elgin newspaper account indicated that whereas Peerless made its own mechanisms, it had, by this time, returned to purchasing at least some of its cases. To the contrary, Seybold was making its own cases and buying its player mechanisms.

This account finally sheds some light on how a Peerless Wisteria could have the same case as a number of Chicago-based competitive models. The odds are that Seybold is the heretofore anonymous maker of that beautiful case style.

The merged firm was called the Engelhardt-Seybold Company with its main offices in Chicago. Elgin newspaper accounts indicate that Frederick Engelhardt indeed succeeded William Grote as president, although we know from St. Johnsville news clips that it was Alfred Engelhardt who relocated to Chicago. Fred Ackermann continued to operate the Elgin plant.

Where Did It All Go Wrong?

Alfred got his Chicago factory. In February of 1914, he actually relocated with his family to Chicago. But there was a catch. In his thirst for action, Alfred hadn’t gotten the full picture on Seybold’s financial condition. Apparently, Seybold was in a lot worse shape than was known by the Engelhardts. Deteriorating financial condition may have been the motivation behind Seybold selling out so quickly. One can only surmise that Alfred’s inexperience at acquisition resulted in a hasty decision.

Perhaps it was hastiness, perhaps it was opportunism caused by the receipt of cash from Link or perhaps it was due to an eroding grip on an increasingly competitive market, but within 18 months of the acquisition of Seybold, the whole conglomerate toppled into bankruptcy.

It’s an amusing strategy Link unwittingly executed. Give your competitor enough money to hang themselves with!

Grayce Knack, Walter Engelhardt’s secretary, was interviewed in early 1984. She recalled:

“Alfred went out of town often (in 1913). He attended to legal matters and once, upon his return, we learned the Engelhardt’s had merged with the Seybold Piano and Organ Company of Elgin. I had no previous knowledge of any such transaction. Alfred was seldom in the factory (in St. Johnsville) after this. I assume he stayed at the Seybold plant. Business went on as usual and I knew nothing of the failure until I was told we were closing Engelhardt and my services were discontinued.”

Other recollections of the 1915 collapse come from a paper written by an Engelhardt contemporary, Robert Rowland, entitled

Memories of St. Johnsville:

“There were several of those Peerless players and orchestrions around town. Jones S. Smith had a flourishing music store business for years, corner of Washington and Main. . .he had a very large stock of pianos.. .for a time he had a very largePeerless orchestrion on exhibition.

When that thing started up like a brass band, mandolin, piano, drums, etc., the whole of East Main Street shook! Then there was another in the orchestra pit of the opera house. I never heard that one, but I would have thought it would tear the building apart judging from its size. I think there were several around town . . . In any event, the whole thing flopped. They must have all conked out together and most families left town.”

From an April, 1916, issue of the St. Johnsville enterprise we learn:

“The peak of business was in 1912, gross sales were well over $500,000 a year (note: at $400 average wholesale/machine = 1,500 machines/ year). The entire business was built up from the profits of the business, and but for entangling alliances which are now past history, the business would have been here today. As long as the Engelhardts were contented to operate the business here at home they always made it a success.”

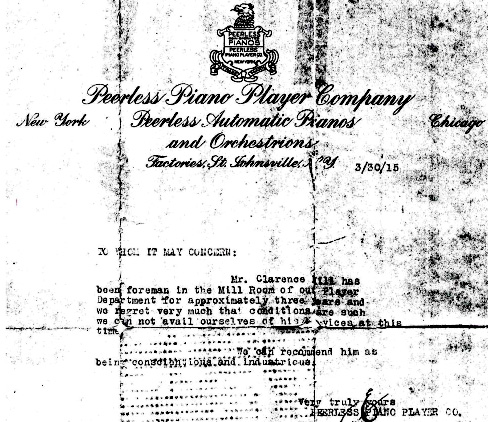

Fig. 23: A sad ending to a great musical venture. This letter dated March 30, 1915,

and signed by Alfred Engelhardt is a reference for Clarence Hill, the foreman of the mill room of the Player Department because: “… we regret very much that conditions are such we cannot avail ourselves of his services at this time.”

Some notes on Peerless from Art Sanders, owner of the Musical Museum of Deansboro, New York, are pertinent:

“Years ago when we were starting our collection of nickelodeons … we happened to find three or four Engelhardt machines. All were in very poor shape. You know the type that sat in mud in a barn for thirty years … We knew some people in St. Johnsville, and through a lot of visiting and digging, we found that when the plant closed, the foremen were allowed to take what they wanted in tools and parts. Most took only tools they could use in other work, but some took parts and pianos.

One man took about 50 stained glass panels of various sizes and made a grid-type ceiling to hold them with light above—really quite a sight. We were able to get this ceiling, plus some six clocks, including the time clock, several pumps and roll frames and other piano parts. Most of all this has been sold.

We talked at length with Mr. Kornbrust who operated the Peerless factory at the last. We never did find a distant relative of the Engelhardt family.

We did talk at length with some of the people, mostly women, who worked in the plant. It was fun to hear them tell what they did and how the Engelhardt family gambled away the profits.”

The reference to gambling comes up more than once when talking to people who were remotely familiar with the Engelhardts. However, no hard evidence supports any theory about the failure of Peerless other than simple business errors in judgment. Alfred Engelhardt always wanted a Chicago base and, when the funds became available, he moved too quickly into an ill-advised acquisition—a story that happens all too often even today.

Is This the End?

Peerless went bankrupt in 1915 when the coin piano business was still booming. World War I interrupted the entertainment business for a few years, but it would be 12 more years before electrical amplification would be developed for the phonograph and radio. The selectable-tune, electrically-amplified phonograph (jukebox) and the radio were to be the death knell of the coin piano industry by 1930.

So, in 1915 the remains of Peerless still had value: market recognition, skilled people and an inventory of equipment, parts and cases. Several businesses were destined to rise up out of the ashes.

Companies such as the National Music Roll Company, E. P. Johnson Piano Company and the Engelhardt Piano Company were prominent in the Engelhardt story after 1915. They are now covered including the discovery of an original Engelhardt Banjorchestra in a follow-up article at: https://www.rickcrandall.net/engelhardt-banjorchestra/