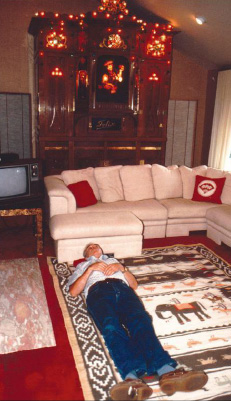

Hayes, McClaren, restorer of the Popper Felix, resting after nearly a year of restoration and then bringing it to the Crandall home.

Nearly 31 years ago, in the fall issue of 1983, this journal featured an article by Rick Crandall describing his adventure finding and researching the Popper Felix while having it restored. Since that time, many things have changed, but some things have stayed the same.

One of the most notable changes is the change in the ownership of this unique automatic musical instrument. The Popper Felix is now in the collection of Jim and Sherrie Krughoff and has moved from Rick Crandall’s prior home in Yipsilanti, MI, (now living in Aspen, CO) to Downers Grove, IL.

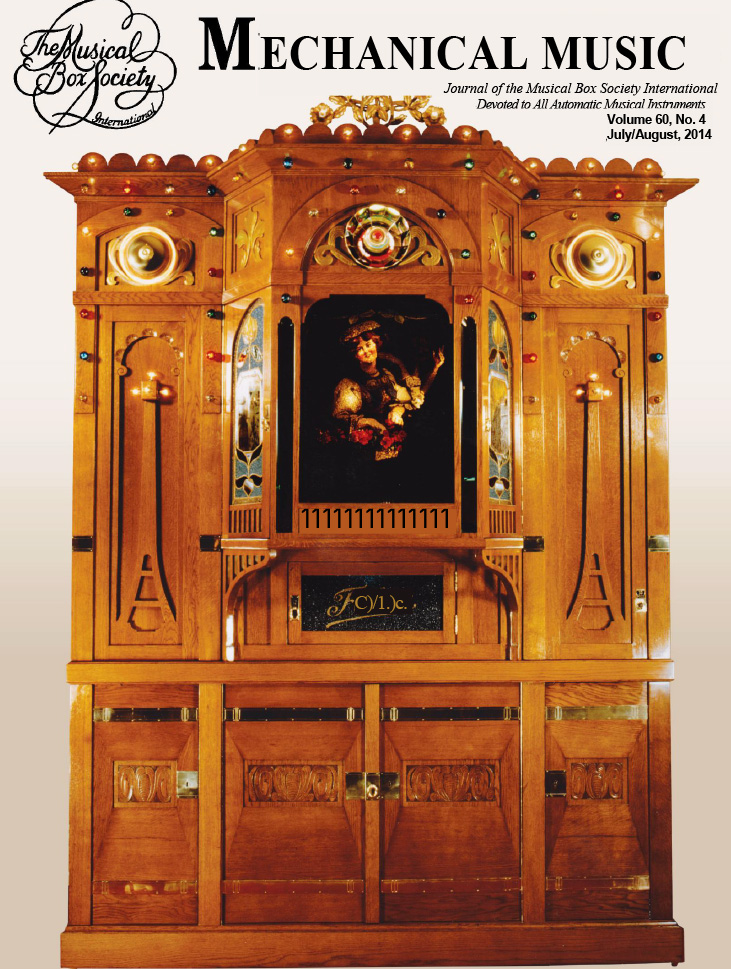

“On Oct. 16, 1987, approximately 50 Mid-America Chapter members were standing in front of a very large orchestrion in the home of Rick Crandall in Yipsilanti, MI,” Sherrie Krughoff remembers. “We jostled one another to gain a vantage point to be able to see the moving scene. We all stood there – mesmerized by flashing colored lights – while a beautiful woman tossed roses from a basket over her arm and blew kisses to the crowd. That was the first time we ever saw the Popper Felix. Jim was particularly interested in large orchestrions. Being one-of-a-kind made it even more desirable.”

“It is a very stable machine,” Sherrie said. “It has only required piano tuning and we have purchased a lot of colored light bulbs.”

“We play all types of music. One of the most popular is a special roll arranged by Art Reblitz. It includes: “If I Were a Rich Man” from “Fiddler on the Roof,” “The Original Boogie Woogie,” and the “Michigan Fight Song.”

“Architectural styles of cases vary from machine to machine. Felix is very special. When people are visiting our collection, Jim explains to them that Felix, with its extensive light show, was built just as the German people were getting electrical lighting in public places. This gives our visitors a time reference regarding the popularity of mechanical music. Also, the Rhine castle, on one of the painted panels, at the side of the moving scene, sits directly across from the home of some dear friends in Rudisheim, Germany. Its popularity among our visitors is demonstrated by the fact that its performance is always followed by applause.”

Mechanical Music has also changed significantly as today’s digital desktop publishing software is many times more powerful than the software of 30 years ago. That allows for the presentation of material in ways that was hardly dreamed of three decades ago, at a fraction of the cost. Mechanical Music now prints in full color instead of black and white, and it prints six times a year instead of four.

Things that have remained the same through the years are the Popper Felix’s quality and rarity and the engaging nature of the story told by Rick Crandall.

Considering all these factors, we have chosen to reprint Rick’s story in the following pages with a few minor updates to the text, but with a significant number of additional color photographs that show details of the Popper Felix that may never have been seen by readers of this publication.

The photos on these two pages alone are a case in point. In the upper right of this page is a photo of Hayes McClaran resting on the floor of Rick Crandall’s former home after completing the installation of the machine in the only room with a ceiling high enough to accommodate the 11-foot tall work of wonder. The restoration took McClaran nearly six months of solid effort. He poured his heart and soul into returning the Popper Felix to a condition that ensured it will continue to entertain people for many years beyond his career. The photo wasn’t printed the first time this article graced these pages, possibly because of a lack of space or the fact that it would not come across as clearly in black and white. But now, in full color and knowing the story behind it, the photo conveys a great piece of this whole story, it shows a master craftsman experiencing the elation and exhaustion of a job well done and taking a well-deserved rest.

The photo of Flora, the flower throwing girl from the front of the Popper Felix, is similarly spectacular in color and might not have been so great in black and white. It’s wonderful now to be able to see the rich color and detail in the photo so that we might appreciate the artistry that went into creating both the painting and the animation.

Let’s not delay any further. Please enjoy reading Rick Crandall’s piece and looking through all the great photos.

– Russell Kasselman

So here’s to Popper Felix An American Saga

By Rick Crandall

It all started with a nugget of gold. Eureka, Comstock, Virginia City and Nevada City – all are towns whose roots go back to the post-Civil War days when men commonly pulled a pound of gold a day from the creeks of the “mother lode country.”

In 1850 the inhabitants of one California settlement gathered to name their rapidly growing ville “Nevada,” after the nearby, snow-covered mountains. Fourteen years later they met again to deal with the conflict in names with the adjacent state of Nevada, newly admitted into the Union. They solved the problem by affixing the word “City” after Nevada to distinguish their town.

Nevada City grew during the most boisterous of times to become one of California’s boom cities because of the ore in the area. Extravagant sums were spent building homes and business establishments in grand Victorian style, many of which can still be seen today.

After the turn of the century, mining of silver and other ores was combined with lumbering to maintain prosperity. The town attracted all sorts of residents, many of whom were the rugged men typical of a western mining town. In the evenings you would find them in the Council Chamber Bar in the middle of town or on the corner of Pine and Broad Streets, looking for a drink. Tavern and saloon owners made a good living for themselves, but they had to make it their occupation day and night. Saloons and cafes were focal points in busy towns, but they still experienced turnovers in ownership for a variety of reasons including owner fatigue, retirement and lack of financing.

In the year 1911, in Nevada City, just such a turnover took place, making way for Ernest Schreiber to fulfill his ambition to become a proprietor by purchasing the Council Chamber Bar.

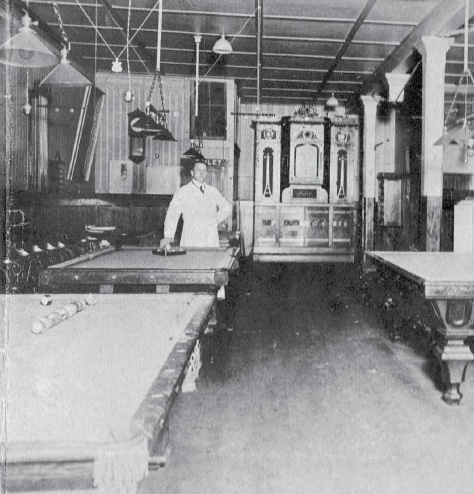

Ernest Schreiber in his cafe in Nevada City, CA. The Popper Felix is in a prominent location behind the pool tables where it played for 20 years.

He dubbed the establishment the Bismark, but later it became known as Schreiber’s Restaurant and Café.

Schreiber was born in 1881 in Wuppertal (called Elberfeld then), Germany, 25 miles from Cologne. He struck out for America and landed a job at a restaurant in San Francisco. Every day he served some of the interesting people who came from a mining town in the Sierra foothills, where the streets were reputedly “paved with gold.” So to Nevada City he went to further his fortunes.

Schreiber’s Café

Immediately on purchasing the Council Chamber Bar, he went about the task of setting up the bar, poolroom and restaurant in the style he wanted.

In 1912 he started serving meals. His slogan, “Everything of the Finest Kind,” was soon known to all. Schreiber’s Cafe preserved the “gold rush saloon” motif with its long bar (along which he would slide brimming beer mugs) and fancy pool tables that today are prized pieces in collector’s homes.Nevada City townsman Bob Paine recalls in an article he wrote for the Nevada City Nugget: “Everything in the place sold for 10 cents: Lee Stanley and Woodpecker Cigars, 10 cents; stein of beer, 10 cents. He (Ernest Schreiber) imported Arthur Allerman from Switzerland to be his chef – one of the best in this country of gourmets. Grass Valleyans by the dozen came on coin-operated machines in the world for his café.

Ernest Schreiber and his wife.

the electric street car on Sundays for a six-course dinner, all you could eat for 24 cents per person.”

Ernie Schreiber presided over the evening activities, tending bar, keeping order and ensuring that everyone had a good time.

He always wore a white, floor-length apron, as though bar-keeping was a scientific activity.

If there was a science involved, then part of the formula for success was music, and so he journeyed back to his homeland to find one of the finest

Who was Hugo Popper?

Hugo Popper started his career in the German military but soon found he was more interested in business. He made one fortune in sales before founding his own company, Popper & Co., in 1890 at age 34 in Leipzig, Germany with partner Hugo Spangenberg.

Always drawn to musical pursuits, Popper saw the coming popularity of automatic musical instruments. He sold more Polyphons out of his distrib-utorship than the factory could keep up with and began to build his own machines. By 1897 he was well-respected for his role in promoting the auto-matic music industry.

He partnered with M. Welte & Sons to create the first reproducing piano and then convinced some of the era’s most popular and well-known artists to record their performances so that they could be shared with the world via his pianos.

He made many orchestrions and called them by names like Othello, Eroica, Mystikon, Con amore and Matador.

– Sources: Encyclopedia of Automatic Musical Instruments, Q. David Bowers and Grassi Museum Fur Musikinstremente

The Popper Felix in Germany

Schreiber was in his home town of Elberfeld in 1921. As Bob Paine recollected: “He came home to Broad Street with a German musical novelty that was to delight the patrons of Schreiber’s corner for many years, a music box playing perforated musical rolls that became famous as Felix.”

Schreiber may have been purposefully looking for a coin-operated orchestra, or perhaps he just stumbled on one that met his criteria of “The Finest Kind.” He did, in fact, end up buying a large classic machine built by one of the leading automatic orchestra manufacturers, Popper & Co. of Leipzig, Germany.

How he heard of the German Biergarten near Cologne, we don’t know, but there he found an establishment financially devastated by the effects of World War I. This establishment was, however, still in possession of a most striking music machine – the Felix, a Popper & Co. model originally built during the years 1906 to 1908. The machine appeared awesome at first, at 10-feet high, 7-feet, 1-inch wide and 4-feet deep, it was noticeable.

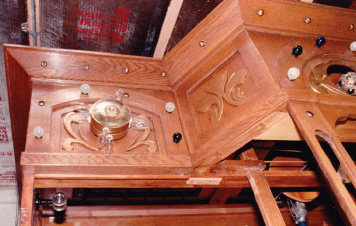

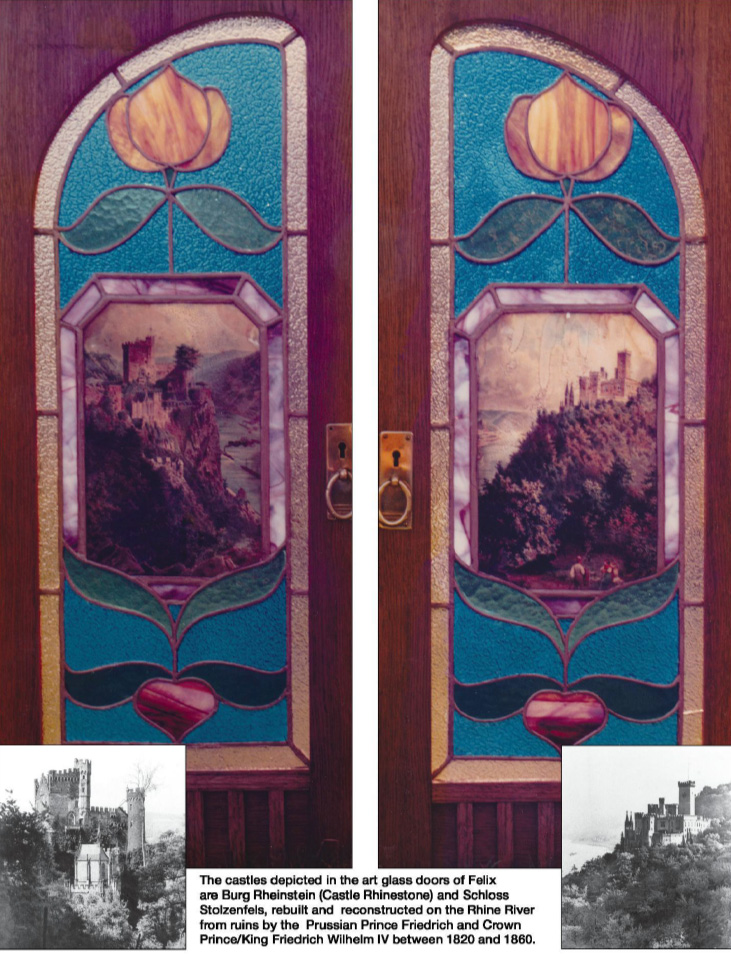

A large bay window adorned the upper-central part of the machine with a seemingly plain window in front and two beautiful art-glass side panels, each with a colorful picture of a famous castle on the Rhine. Below the bay window was the little door to the roll frame, made of crinkled, deep blue glass with a gold script “Felix” in keeping with Popper’s practice of individually naming its machines.

Near the top center of the oak case was a rotating brass and jeweled wonderlight that showered the room in colored light beams when turned on. Adding another 12-inches in height on top of the case was a hand-wrought, gold-leafed metal sculpture of a floral bouquet inlaid with sparkling lights.

Initially, with the machine turned off, Schreiber may not have noticed the 90 colored light bulbs that lined the entire upper perimeter of the case, but they were ready to surprise and entertain him. At some point, he would have noticed the small brass plate framing a coin slot with the instruction, “10 pfennig.”

With the drop of a coin, Felix literally came alive. Schreiber maynot have known what to look at first. Undoubtedly, his eyes would have been transfixed on the bay window in which, almost magically, a beautiful woman appeared with a basket of flowers in one hand. The brilliantly-colored, painted picture would then have seemingly started to move. He would have seen her move her hand to the basket, take out some flowers, and throw them to the audience! At some point he would have been distracted by the perimeter lights flashing alternately in a sequence, all controlled by the mysteries within.

The wonder light rotated and threw off jeweled rays of colored light. Two layered, round brass fixtures also rotated with oblong light bulbs creating a pinwheel effect. The overall feeling created was one of Felix sparkling in a dimly-lit room with a beautiful woman throwing flowers while inviting all to come and listen.

Listening was the best part. Once the music started, Schreiber would have found Felix had muscle. An orchestra of violins, flutes, viol da gambas, cellos, piccolos, clarinets, mandolins, piano and percussion including bass and snare drums, tympani, triangle, Chinese cymbal, xylophone and orchestra bells began to play a wide repertoire of music. Whether it was a waltz, march or a 20-minute opera piece that he first heard, it must have been enough for him to make the decision to buy Felix for his cafe in Nevada City.

Before long, Felix was on its way by boat to California. in pioneering tradition, it traveled through the Panama Canal, which at that time had been open for business for only five years. The boat trip for Felix ended on the northern California coast, and from there it proceeded by narrow gauge railroad to the “mother lode country.” Little did anyone know then, but that trip was undoubtedly responsible for the survival of Felix, since most large machines did not make it through wars and reconstruction in Europe.

Popper Felix in Nevada City

Felix arrived in Nevada City during the summer of 1921 with its art glass and instrumentation amazingly intact.

Once installed and working, it became an integral part of nighttime Broad Street.

Bob Paine recalls: “I am sure the mysterious insides had hundreds of working gremlin musicians. The mechanical orchestra could play “The Parade of the Wooden Soldiers,” “The Blue Danube,” and all the Strauss waltzes. It took 20 minutes to play the opera

“Carmen,” the roll was 200 feet long. Suddenly, little lights would come on in back of the colored glass front and a girl would appear to throw roses at the listener.”

Felix must have been installed and working by the fall of 1921 since a scan of the local newspapers at the time uncovers one ad and several mentions in the “Brief Happenings” column in the Nevada City Nugget:

September 16, 1921 – “When you go to Schreiber’s Restaurant for a meal, you are assured of the very best of food and service. A new addition to his place that is taking well is a piano-orchestrion which he has installed.”

September 25, 1921 – “If you haven’t heard the new piano orchestrion at Schreiber’s Restaurant and Cafe, you have missed a real treat in high-class music. He has a fine variety of choice selections for the instrument which is an added attraction to his already popular cafe.”

September 30, 1921 – “Have you heard the new piano-orchestrion at Schreiber’s Restaurant and Cafe? If not, you have missed a rare treat in the line of choice music. He has an excellent selection of music for this instrument, ranging from jazzy dance pieces to overtures.”

Felix played almost non-stop from 1921 until 1941, an amazing 20-year service record. Schreiber located the machine such that it faced into the bar, and the back of the machine faced an opening into the restaurant. A nickel worked hard in those days Felix entertained two sets of patrons. In fact, I’ve learned that wall boxes were installed at each dining table so diners did not have to go into the bar to hear Felix play. The four Schreiber daughters would often come to the restaurant in the evenings so they could drop a nickel in to hear their favorite roll.

Felix Leaves Nevada City

hi 1941, Schreiber, at age 60, found the onslaught of World War II made it difficult to find anyone who could keep Felix running. He sold the old music machine to R.M. Stagg to be part of a museum of music machines and guns in Reno, NV.

When Felix left town, it was big news and sad news, as evidenced by this excerpt from the local Union newspaper in 1942:

FELIX TO PLAY FOR DOLLARS IN RENO

Early yesterday afternoon, Nevada City bid farewell to “Felix,” the mechanical Orchestrion housed for nearly a quarter of a century in “Schreiber’s Cafe.” It was carefully dismantled and loaded on a trailer by the new owner, R.M Stagg, who will make the remarkable old player a museum piece to furnish entertainment for lovers of fine music.

“There’s a thousand dollars’ worth of music going with it,” the new owner said, adding “the masterpieces of German composers, the marches and the operas America has come to love.”

Friends coming and going for two days since word of the sale got around, are concerned over the loss of a favorite source of entertainment.

The new owner has his museum, the “Old Corral” at Mountainview along the Bay Shore Highway, but plans to move to Reno to open what will be known as “The Bell of Reno.” Felix will no longer play for nickels, according to the plans of the museum collector, but for dollars. When properly set up, the entertainment will include lighting effects and even a dancing figure. All that the famous organs, the operas and world renowned orchestras have to fine music lovers, this German made orchestrion will be able to reproduce, according to the opinion of the experts. “This one is an especially rare example,” Stagg remarked. (sic)

Crandall, upon first sight of the Felix, lighting from the interior to inspect Flora, the moving art scene.

Various pictures of the interior and disassembled components gave a first impression that most if not all of the machine was present.

In the late 1940s, Stagg’s entire collection was sold to a gambling and entertainment club in Reno. Along with Felix were other music machines including a Seeburg G, Seeburg J, Seeburg Kr, Wurlitzer CX, Coinola CO, Mills Violano, Multiphone, Welte Cottage orchestrion and a hoard of cabinet machines. They were all stored in a corrugated-metal storage building right in the middle of Reno, and there they sat for 35 years, forgotten and unnoticed. For all practical purposes, Felix had disappeared from the face of the earth.

While in hibernation it was becoming even more of a museum piece, and an antique as well. Beginning in the 1960s, collector interest developed in automatic music machines, and by the 1980s Felix had unwittingly become one of the world’s few remaining prizes in its field. But it languished in its shed until a local citizen, claiming he could smell antiques in those buildings from his car as he would periodically drive by them, finally satisfied his itch by gaining permission to look inside. There he saw a hoard that was enough to open anyone’s eyes. He proposed an exchange for the one machine too big for use in the club … the Popper Felix.

Discovery!

So in 1978 the machine surfaced, but remained unknown to the automatic music collector community. The new owner was apparently thinking about restoring the machine himself, but it was far too complex for him. He’d heard of Hayes McClaran, the well-known Fresno, CA restorer and would occasionally call him with questions. Knowing Mac, I’m sure those were short conversations.

One day in 1981 I had an MBSI meeting at my house in Ann Arbor, MI and Mac came to the meeting. He was impressed with the collection I had at the time and the quality of the restorations on each of the machines (mostly done by Dave Ramey, Sr.).

Mac said to me, “I’d like to find something for you and restore it for your collection, what don’t you have?” Well I had enough American machines so I wanted one, hopefully impressive example of a European orchestrion. He said, “Well, there’s a guy who keeps bugging me with questions about what’s this and that, clearly he doesn’t know what he’s doing, but judging from the questions, he’s got something big and it’s European.” So Mac gave me the lead and I bird-dogged it for months, finally making a connection with its owner.

All I got from him was a single Polaroid, not well lit, but you could tell the machine was big and it was a Popper and it had lots of visual action all over the front of the case. It had to be big for a reason (i.e. lots of instrumentation) so I got excited, but he didn’t want to sell. How many collectors have run into that problem? So I kicked into a time-tested strategy (I have many), I asked him: “Clearly you’re not a music-machine collector, you have just this one machine, what do you collect?” To which I got the answer: “World War II military artifacts.” I had no idea what that meant, but I pressed forward: “OK, what military item don’t you have that you would really like to own?” He said, “that’s easy, a German half-track tank.”

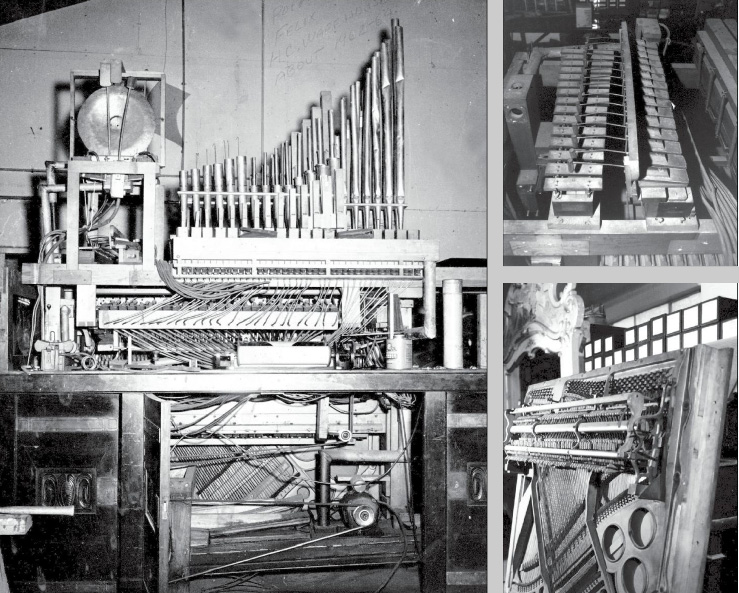

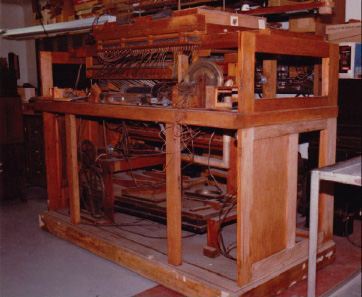

The lower half of Felix at McClaran’s workshop.

More parts and pieces of the machine in the workshop.

One of the side doors showing an Eiffel Tower carving.

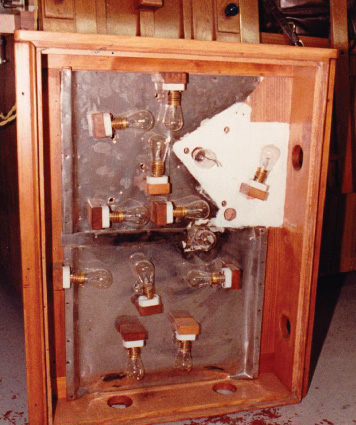

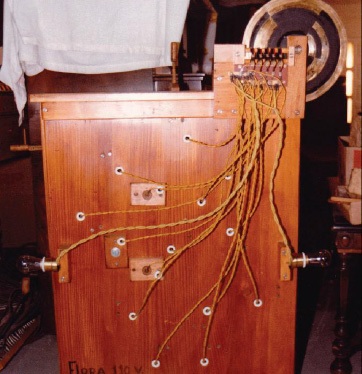

The lighting arrangement for Flora, the flower girl.

Close-up views of the spinning light wheels that create a pinwheel effect.

The wiring setup that animates Flora’s action of flower throwing. The animation can be set so that Flora looks like she is throwing flowers to the audience or catching them from the audience.

Flora’s arm is shown in all three positions.

I asked him if I found one for him would he trade the music machine for it? He said something like “in a heartbeat!” in a tone as though he thought I was crazy. Of course I had no idea how to find a German half-track tank, but I knew that any collector who wants something, probably knows where some are, so I asked him “Can you give me a list of where some are?” to which he responded, “I only know where there are five in good condition.”

So you know the rest of the drill – I got the list and contact info, most were in Europe. Sure enough one was owned by an older guy in Scandinavia somewhere and he was willing to sell – for a price that was undoubtedly high for a half-track tank but not much for a large European orchestra. For that kind of money I was willing to take a gamble that the machine was big enough and complete enough to go for it.

Well to cut the story down, I got contracts signed all the way around (because I didn’t want to own that half-track tank for even five minutes) and the Popper became legally mine. The former owner had completely dismantled the machine so what I owned turned out to be a hulking case with many cartons of parts and pipes.

But it wasn’t until McClaran and I showed up in a rented 22-foot truck with hydraulic rear lift at Felix’s hiding place, opened the garage door and saw the huge case and cartons of parts that I realized how unique it was. We unpacked all the cartons and laid out the pieces on the floor. By the time we were done, we saw that Felix had six ranks of pipes (158 in all), and it was truly one of the few remaining large concert orchestrions made by Popper.

The amazing part about the find was that after all those years and all those trips, including a boat trip in 1921 across the Atlantic and through the Panama Canal, 157 of the 158 pipes were still present, and all the art glass was intact! Felix deserved nothing less than a total restoration to be returned to the status of a grand orchestrion.

I was overwhelmed at first with the idea of a machine with such credentials. The next day we settled into the task of dismantling the machine and packing it safely onto the truck for transport back to Fresno.

While McClaran began planning the restoration, I researched the origins of Felix. Werner Baus and Hans Schmitz came to the rescue. It was Hans who learned the castles painted on Felix’ art glass were Burg Rheinstein (Castle Rhinestone) and Schloss Stolzenfels. These were two of three particular castles on the Rhine (the third one is Burg Sooneck) which were rebuilt and reconstructed from the ruins by the Prussian Prince Friedrich and Crown Prince/King Friedrich Wilhelm IV between 1820 and 1860.

That was a period of national renaissance. The culture and fine arts of the period being referred to as the “Biedermeier” style.

Finally, the prize piece of literature surfaced: from Werner Baus I received a copy of a 1908 Popper catalog page, and there was Felix! The Felix from Nevada City was identical to the catalog except, instead of the woman throwing roses, the catalog machine seems to show a costumed actor with moving arms. Indeed, the catalog description spends equally as much time describing the lighting effects as the complement of instrumentation.

Popper & Co.

The only existing large Poppers known to this author are the Gladiator and the Salon Orchestra at San Sylmar, California, the Luna in the Werner Baus collection, and the Iduna in the Doyle Lane collection.

Popper & Co. was a leading automatic musical instrument firm from the 1890s to the 1930s. In the year 1911, (coincidentally Schreiber’s Cafe was just opening and Felix was just two years old), Popper & Co. received an award for the quality of its music machines in Turin, Italy, as evidenced by the following article in The Music Trades Review:

GRAND PRIX FOR POPPER & CO.

Leipzig House Honored at Turin International Exhibition Leipzig, Germany, October 15, 1911. Popper & Co., manufacturers of automatic instruments, has been awarded the Grand Prix at the International Exhibition in Turin, Italy, on account of first class construction and artistic abilities. Since the foundation of the house, Popper & Co. has received the following awards:

Prize of Honor from the King of Saxony, Five State medals, a number of gold medals from numerous exhibitions.

From the Encyclopedia of Automatic Instruments (Bowers, The Vestal Press, 1972), we learn:

“The most spectacular of all Popper instruments were the huge piano orchestrions of the 1900-1920 era . . . these large Popper orchestrions are interesting for some of their unusual effects . . . the Con Amore orchestrion displayed tiny mechanical birds which fluttered and tweeted while the music roll rewound so the patrons would not lose attention during the normally silent rewinding period.

“The arrangements on Popper & Co. orchestrion rolls are excellent, for the most part, and collectors today consider Popper instruments to be among the finest orchestrions ever produced.

“These huge Popper orchestrions, once made by the hundreds, are exceedingly rare today.”

Popper Roll Arrangements

As with many music machines, Popper roll arrangements had differing characteristics between early rolls (#1-1999 – circa 1908-1918) and later rolls (#3000 and 8000 series, post-World War Ito the early 1930s).

The earlier rolls made more elaborate use of pipes for string, wind and reed instruments to achieve variations in musical “color” similar to actual orchestral arrangements. Apparently the earlier music arrangers were educated in real orchestra-arranging strategies. The fullness of the music contained in a Popper roll can really be appreciated on the Felix, particularly the way the rolls employ the clarinets, piccolos and bells.

In real orchestras, the piccolo is the shrillest of instruments. Its brilliant tone color is almost always used for picturing frenzied merriment, infernal rivalry or other climactic passages. Popper arrangements use the piccolos sparingly and only when powerful, bright highlights for musical peaks are needed. Without the piccolos, the Felix has variety and a normal range of expression, but when piccolos speak, fire rages and the blood rushes.

The clarinets set the Felix apart as they would in any machine because they add full, mellow color. The richness of the clarinets makes Felix’s music sound full without being loud. Solos on the clarinets are very effective.

Popper arrangements use the viol da gamba (soft) and violin (loud) ranks as the workhorses of the music, as in a live orchestra. Expression is achieved either by playing the gambas only (which are soft and subtle) or the violins (louder) or both.

The cellos are really a bass extension of the violin rank. They are the base line of the orchestra and are used for depth and presence, never as a featured instrument.

The flutes are versatile and clear with medium power. They are also workhorses and used for livelier portions of the music. When used in combination with the violins, they mold another component of expression.

The bells or glockenspiel are metal bars struck with metal beaters. They have a bright, lingering sound, especially effective for tuned accents, and are used sparingly.

The piano in the Felix is powerful. The bass is rich, noticeable and almost always present. The piano bass and the cellos provide the bass component of the music. The piano treble is separated from the bass and is used for piano solos, for melody accompaniment, and at times is turned off to let some pipe rank or the xylophone perform a solo.

The xylophone is a 27-note, single-stroke instrument with wood bars and wood beaters. It has a great sound and is often used with popular songs. One later jazz roll actually plays “The William Tell Overture” on the xylophone with great results.

The above comments apply to the original Popper factory arrangements, but not to the Belgian arrangements. The latter are quite different and far less complex. They play the Felix like a small band organ, using the flutes more often than the violins and almost ignoring the clarinets and cellos. In this author’s opinion, the only redeeming quality of Belgian arrangements is that some tunes are well-known American songs that strike a familiar ring in the U.S. collector’s ear.

Early original Popper rolls covered a broad range of classical, dance and novelty music. The classical songs are exciting and rich as are some waltzes; whereas other waltzes and the marches are repetitive and were clearly meant more for dancing than listening.

Happily, the Popper arrangements use only the instrumentation needed at the moment, rather than having to bear down on the listener with all it has all the time. The effect can be likened to a lightweight prizefighter dancing, bobbing and seemingly able to invoke any of his resources at will, with grace and selectivity.

Later rolls have similar sparkle, but lack the fullness in the pipe section. These later arrangements catered to the changing nature of the machines being produced -with greater emphasis on piano and percussion (xylophone and drums) and less on wind and string instruments. The arrangements are often “jazzier” and less serious, but definitely fun to hear.

Fortunately, a surprising number of American tunes can be found in both early and late rolls, including Sousa marches, show tunes and even familiar songs such as: “Broadway Melody,” “Fascination Waltz,” “Ramona,” “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” and “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby.”

The layout (scale) used in Popper rolls maintained surprising consistency over the 25 to 30 years that rolls were produced, and the orchestra roll was compatible with all sizes of orchestrions. The only real change was the addition of piano-stack expression (high and low vacuum) on later machines which supplemented the loud/soft hammer-rail expression. According to Werner Baus, this extra level of piano expression was added when Popper had a falling out with Welte and brought out the Popper Welt, an expression piano/small orchestra competitor to Welte.

Another modest difference in the later jazzier machines is the addition of a woodblock. Care must be taken when playing early rolls on later machines since the hole used for the woodblock controlled a pipe register in earlier days.

The compatibility of Popper rolls across a broad line of orchestrions has made it possible, through roll cutting, to preserve an extraordinarily broad range of music for the Popper orchestrion. In 1983 there were 200 different, hand-selected Popper rolls in the process of being recut on John Malone’s versatile perforator. The project was sponsored by Werner Baus in Germany and Bob Gilson in Madison, WI. This author’s seemingly endless chasing and auditing of roll collections provided over 550 rolls to choose from.

A Look Inside the Machine

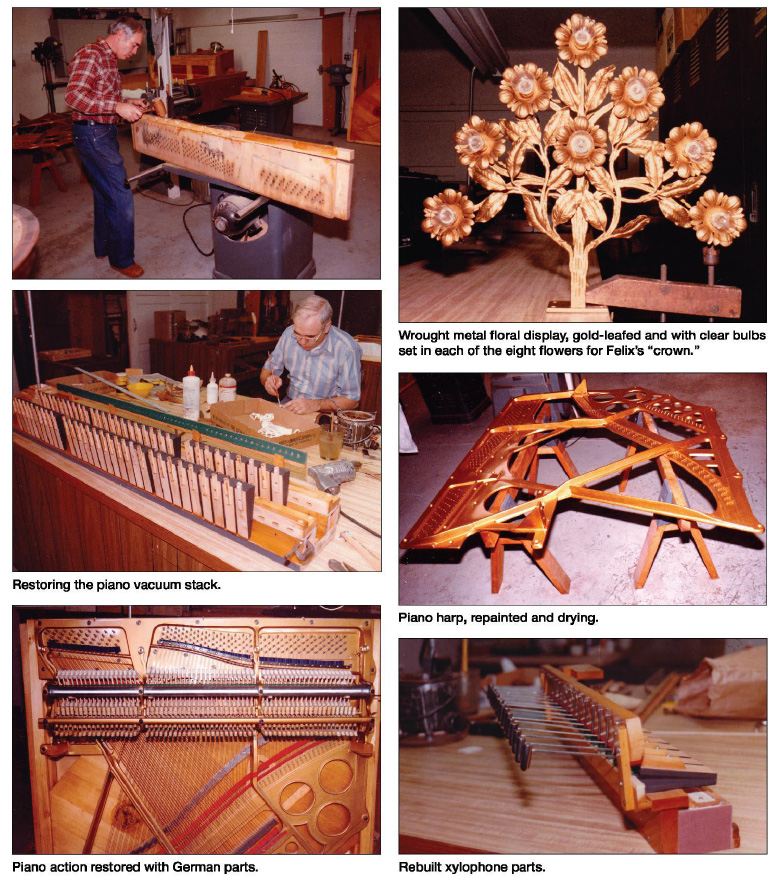

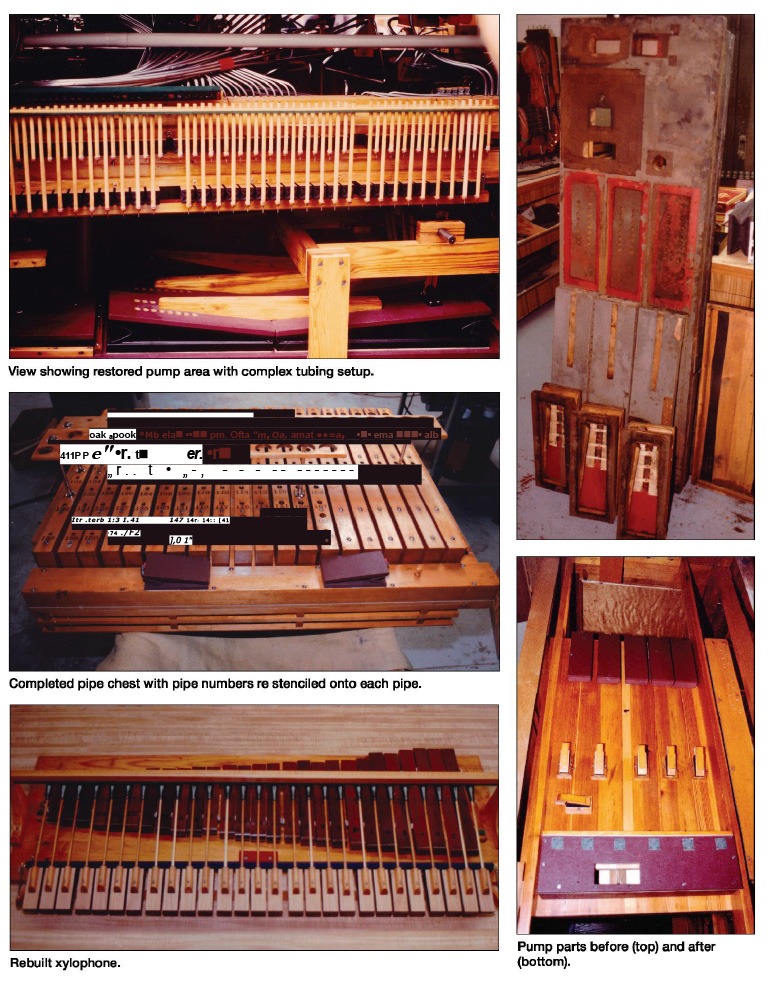

In December of 1982 the restoration of Felix commenced in earnest. In the ensuing months, every corner of the machine was disassembled, investigated, cleaned, finished and reassembled by McClaran. At the end of a six-month effort, everything about the machine was understood.

The Europeans went about orchestrion building with some finesse because musical tastes leaned more toward the classical than in America, where music machines were made for less serious purposes. For instance, the piano in Felix is of high quality as is typical of German orchestras. Usually Feurich pianos were used, but in Felix’ case, the only identifying mark on the piano plate is a Popper logo and the serial number 5022. The plate is identical to an Otero made by the Weber Company, so a good guess is that Popper did not make the piano itself.

Musically, the bass section of the piano has 29 notes, plus the lower five notes are octave coupled. This is where each of the notes in two different octaves is coupled so when a note in the coupled range is called for from the music roll, two notes actually play. This increases the bass richness and power, which is important in an orchestrion that typically depends heavily on the bass in the piano to carry the rhythm of a musical selection.

Restoring Felix

Photos taken during the restoration process done by Hayes McClaran

The treble section is also 29 notes. It is separate from the bass section so the treble can be turned off, thereby allowing a pipe rank or the xylophone to perform a solo in that note range, while the piano bass can continue playing the accompaniment.

Closely associated with the piano is the mandolin rail – literally a rail with leather fingers that are metal tipped and hang close to the piano strings.

The big 25-inch bass drum is struck by a beater at the same time a genuine Chinese cymbal is struck. There are actually two bass drum beater pneumatics with which expression is achieved. If the roll calls for only one pneumatic, a softer sound is produced than if both contribute their forces simultaneously. Snare drum expression is achieved differently by pneumatically controlling how far the beater is from the drum surface at rest; the loudness is thereby controlled. A kettle drum sound is achieved with the addition of two tympani beaters poised over the bass drum.

Accenting is provided by a triangle, a crash cymbal and a 15-note set of tuned orchestra bells. The crash cymbal is the same Chinese cymbal but can also be hit with a felt-covered beater, making a more fully-developed and longer-lasting crash than normal. A third level of cymbal expression is achieved by both beaters hitting the cymbal which results in a noticeable crash. Additional tuned percussion is provided by a 27-note wood xylophone which is often used for solos.

The pipe section in Felix incorporates an interesting and versatile range of reed, flute and stringed instruments. The pipes in an orchestrion are identical to the pipes in an organ. Five of the six pipe ranks which Felix has are of the flue variety. Flue pipes are of the whistle or recorder type whereby air passes through a narrow aperture or flue. The flute is in constant service in the orchestra, taking the melody for the woodwind group just as the violin does for the strings. Often it is combined with the violin for this purpose. This is no doubt the basis for so many orchestrions with one or two pipe ranks always having either flutes or violins.

Felix’ flutes are a wooden, harmonic rank surpassed in pitch only by the piccolo (short for flauto piccolo or “little flute”), which is a half-sized flute used chiefly for special effects. Felix’ piccolos are of the unusual philomela type. They are open pipes with a double mouth, resulting in a high-pitched piccolo that is even more differentiated from the flutes than usual.

Flue pipes are of three classes: diapason, flute and string. Diapason is a generic term for a family of flue pipes that only exists on an organ and has no real instrument counterpart. Felix only has pipes that are imitative of real instruments. This fact, plus the presence of a piano, are the reasons for it being called an orchestrion rather than an organ. For example, three of its flue ranks are of the string type: violins, cellos and gambas. The violins are wood pipes registered separately from the cellos. The cellos are a short rank extending down into the 4-inch range of bass pipe.

On the other hand, the gambas are a longer rank of softly-voiced metal pipes. Gamba is an abbreviation for viol da gamba, (literally “leg viol”) referring to the fact that all instruments of this type are held on or between the knees.

The clarinets are a completely different pipe rank operating with wind passing over a beating reed and a cylindrical or conical resonator.

Clarinets are a mellow reed pipe usually appearing only in large orchestras, and unheard of on American orchestrions.

Expression (loud and soft) is provided in various ways, including a traditional piano loud /soft pedal which controls the position of the hammer-rail percussion expression (as previously described), and overall expression from the swell shutters on the top of the case. Swell shutters are louvers which open and close partially or fully, depending on the length of the control hole in the music roll. These infinitely variable swell shades are uniquely characteristic of certain German machines. A great range of expression is also implemented by careful selection of pipe ranks that are turned on at any point. The piccolos are an expression device all by themselves in that when they are on, they seem to double the volume of the entire orchestra.

European vs. American

I have already mentioned some differences between European and American machines in several passages of this article. It is fascinating that American manufacturers were consistent in their strategy to produce music machines that were truly fun for listening as opposed to the fairly prevalent European strategy of concentrating on more musical realism and intricacy. American machines would usually permit the listener to peer through clear gaps in the art glass to see the instruments play (all part of the fun), whereas European machines were closed up tight as a drum and animated art glass effects were used to entertain the listener.

The most dramatic differences between American and European machines can be found in the roll arrangements. Most American roll arrangements are centered around the piano and music that typified player pianos. Controls for other instruments are added to the basic piano arrangements. Pipes are turned on and off for variety rather than for the aesthetics of the tune. They are snappy, popular and toe-tapping.

German arrangements squeeze the most out of the machinery with a balanced demand for the instrumentation when they are needed in accordance for a more faithful rendition of the original arrangement. Classical and dance music is dominant, which means it is less piano dependent.

As a comparison, take the Cremona J, a top-of-the-line American machine with a complement of instruments identical to the Popper Rex (a Felix minus all but the violins, the flute pipe ranks and the orchestra bells). The Cremona J plays the Cremona M roll that is arranged to solo on the pipes and the xylophone. Listening to the Cremona J and the Popper Rex side by side will separate collectors int two definite groups. There is no right or wrong, just two different styles of music. The American machine was designed to entertain people in saloons with a fun, piano honky-tonk sound, whereas the European machines were meant to appeal to the more refined tastes of their continental patrons.

As a collector, I would never choose one over the other. If a collection can have two principal music machines, it should have one of each. Rarely will you find good American popular music on a European machine, and you’ll never listen to the American machine for original classical music.

Felix Restored

In July 1983, Popper Felix’s restoration was complete. While the machine was being “shaken down” in Fresno in preparation for delivery, Ernie Schreiber’s daughters: Gertrude Murray, Elsie Sharpe, Eleanor Putnam, Louise Geddes and their families were invited from Nevada City to see and hear a distant memory – after a 40-year absence! Once again Felix delighted its former owners by lighting up — as only it could — while providing its best performance since leaving the factory some 70 years earlier.

McClaran and his assistant, Brad Reinhardt, had outdone themselves. Typical of the few top-quality restorers in this field, they felt they had left a permanent piece of themselves somewhere inside Felix’s wondrous innards.

Ernest Schreiber’s daughters gathered in 1983 to hear Popper Felix play again some 60 years after it first arrived in Nevada City.

As McClaran said: “You can’t get through a project like this without having some feeling for the machine and what it once represented. Nearly every glue joint, every valve (all 311 of them) and every piano hammer needed redoing. After years of languishing in a baking-hot shed, Felix needed to be completely disassembled and rebuilt as it was originally done at the factory.”

The restoration took 23 weeks of effort, including deciphering the vast and curious electrical system that controlled all of the lighting and animation. Fortunately for restorers, Renner’s of Germany, a piano supply house, stocks the exact and pertinent for all aspects of the German piano.

Members of an Ann Arbor, MI, high-school football team moving a parts 1,200 pound base up the front stoop and into author’s house.

Hayes McClaran, with assistant Brad Reinhardt, make final adjustments as Popper Felix is installed in its new home.

When it came time for Felix to leave its restoration berth in Fresno, it was McClaran himself who rented a truck and drove it to the author’s home in Michigan. “The machine is restored to the best possible condition and the case has a fine furniture, hand-rubbed finish. There’s no way I could bear to see someone else handle something this large and awkward with the care it should get,” declared McClaran.

On a sunny July day, the Popper Felix was installed in our living room — the only room with a ceiling high enough . I asked my wife (who is not a music collector, but who is very understanding) what she thought of the 11-foot high decoration in our midst. She replied wryly, “Oh, it’s useful to show friends that clearly I’m married to a crazy person!”

A Collector’s Dream

From my perspective, the Felix has come a long way and is now properly restored to play for nickels once again. Its exquisite condition assures its permanence in the world of mechanical music.

The hunt, the discovery, the acquisition, the restoration, the hearing of the first note, the historical research, the scouring for original music, and the preservation of a genuine artifact from the California gold rush territory surely justify the story of the Popper Felix as a classic American saga.

If readers have knowledge of other Poppers, please notify the editor as I am planning to write more on this venerable maker of music machines.